“The sun is gradually expanding,” Elon Musk told a rapt audience in 2013 at SXSW, the famous media, music and technology conference held in Austin, Texas. “In 500,000 million years, a billion at the outside, the oceans will boil and there will be no meaningful life on Earth—maybe some very high temperature bacteria, but nothing that can build rockets.”

Musk, the South African-born entrepreneur, who aims to transform the energy industry, the battery storage industry, the auto industry and the transportation industry also wants to go to Mars. Sure, reaching the red planet would be a stunning feat of technological prowess, but helping the first human being (that we know of, more on that later) get to Mars is not enough for Musk. He wants to do it, literally, to prevent the inevitable demise of the human race. Whether we blow ourselves up in a nuclear firestorm next decade, a comet eradicates all life on the planet next millennium, or it is the sun itself that obliterates the planet in a billion years, Musk foresees an end to earth. And in response to that, he plans to craft a new beginning beyond the reaches of our rare blue-green world. Mars is the first stop. But getting to Mars is just half the battle, the real work entails dying on Mars.

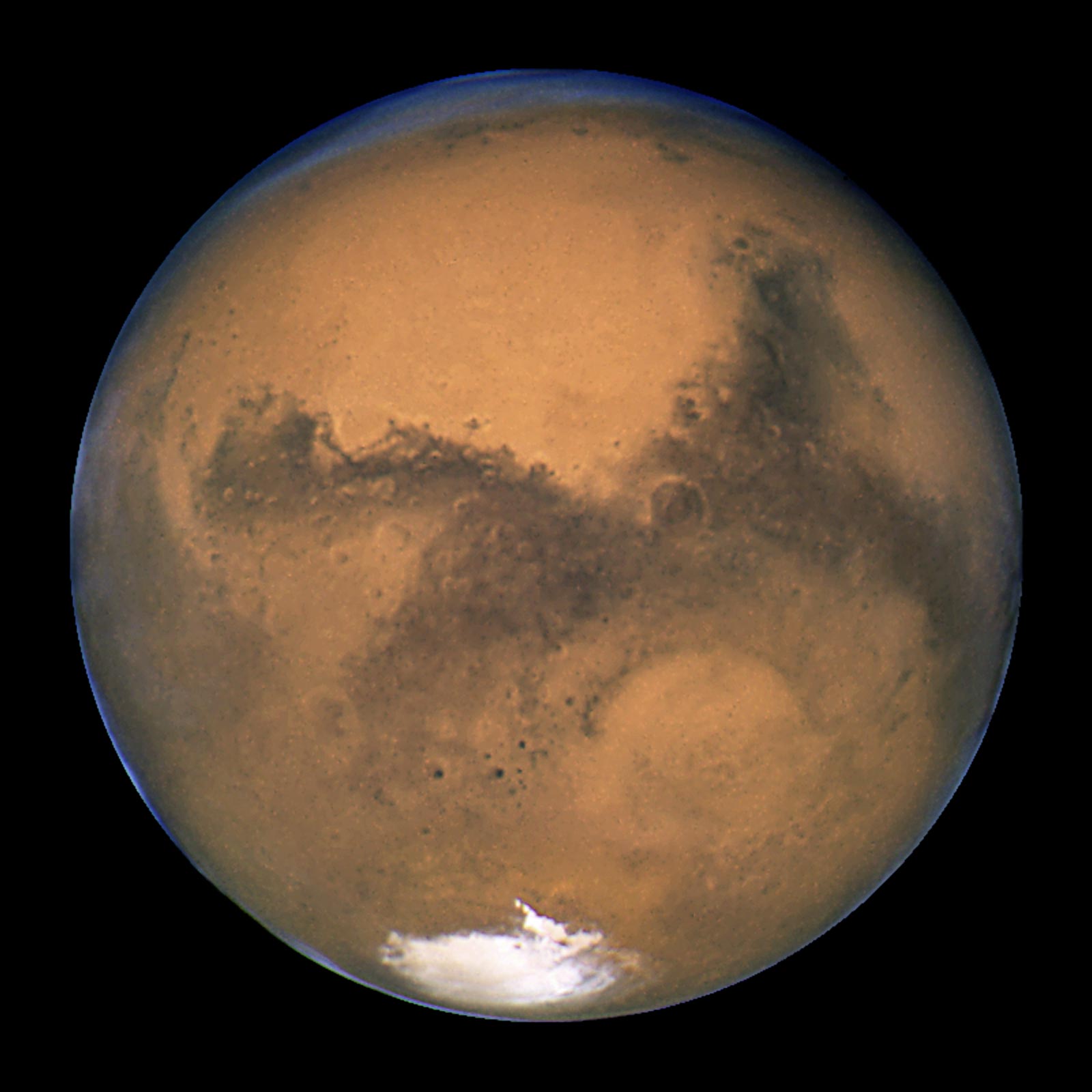

In fact, Musk himself has said he wants “to die on Mars, just not on impact.” It’s a grand statement, but what Musk means is that he doesn’t just want to send a little rover to Mars to play around in the dirt and take samples, he wants to actually build cities on Mars. And not just that, he wants to terraform Mars, possibly by dropping thermonuclear bombs over ice caps at its poles. The goal is that someday human beings will be able to live on Mars without spacesuits, and not just in super futuristic looking dome cities. There will be outdoor parks with trees and flowing streams, fields of agriculture, grocery stores, tattoo parlors, and presumably funeral homes too.

This all raises the question, who will be the first human being to die on Mars?

There appear to be many people jostling for that honor. Who can forget the pitch of the Netherlands-based project, Mars One, which in 2013 put out the call to citizens of earth for a crowd-sourced trip to the red planet? According to the Mars One website, more than 202,000 people responded to the call, from over 140 different countries. It was an exceptional response, considering the very real chance of death in transit to Mars or on the planet itself. Presently, “one hundred Round 3” Mars One candidates remain. But if you missed out, worry not, you can still die on Mars. “New selection programs will start regularly,” reads the project’s website, probably in the first quarter of 2017, “providing aspiring Mars settlers new opportunities to enroll in Mars One’s astronaut selection program.”

Of course, Mars One has a particularly rosy take on the red planet, and what awaits human beings who attempt to travel there, let alone live there. “They’re going to be sick when they get there,” NASA scientist Jennifer Fogarty recently explained to National Geographic, referring to the array of health hazards facing any Mars-bound human. “Bones waste away in zero gravity,” continued the National Geographic article, the cover story in this month’s issue. “The rule of thumb is you lose one percent of your bone mass per month. Vigorous exercise helps, but the jumbo equipment used on the space station weighs too much for a Mars mission. Some astronauts on the station have also experienced serious vision impairment, apparently because fluid collects in the brain and presses on the eyeballs. The nightmare scenario is that astronauts land on Mars with blurred vision and brittle bones and immediately break a leg.”

And there is more. “Radiation is another hazard,” said the National Geographic article. “The astronauts on the space station are still mostly protected by Earth’s magnetic field. But on a journey to Mars they’d be vulnerable to radiation from solar flares and cosmic rays, which are high-energy particles coming from across the galaxy at nearly the speed of light. The latter especially can damage DNA and brain cells—which means astronauts could arrive on Mars a little dimmer, as well as blurry eyed and brittle boned.”

Basically, going to Mars is going to be no walk in the park. It is going to be more like a stroll through a frigid, pitch black, radiation-bombarded wasteland. President Obama understands this. “I still have the same sense of wonder about our space program that I did as a child,” he wrote in an op-ed article last month published with CNN. “It represents an essential part of our character — curiosity and exploration, innovation and ingenuity, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible and doing it before anybody else.” But, Obama added, “We have set a clear goal vital to the next chapter of America’s story in space: sending humans to Mars by the 2030s and returning them safely to Earth, with the ultimate ambition to one day remain there for an extended time.”

In other words, Obama and NASA are taking a much more measured approach to Mars, and are clearly not as eager to get humans all the way there just so they can die. Of course, there are other voices in the room, and one of them belongs to a young Russian named Boris Kipriyanovich, from the town of Zhirinovsk, in Russia’s Volgograd region. Boriska, as friends and family call him, is an extraordinary human being. Apparently, he uttered his first words at four months old and by the age of one and a half was reading newspaper headlines. At age two he started school. It was at about that time the young boy started relaying detailed information on Mars. Perhaps most extraordinary, he remembered his past lives, including a past life lived on Mars more than a million years ago.

“People from Mars traveled in many galaxies and planetary systems,” Boriska explained. “There were ships of an airplane type. They were triangular. There were ships like a drop.” There were ships with “plasma power, ion power. If they used gasoline the fuel ran out too fast, the engines were too powerful.” There was teleportation, in which time “slows down…and opens a kind of a portal where time is speeding up fast…I can’t say exactly. I don’t remember. It opens on one side and in a few seconds or even minutes if the transfer is far away it opens another area of space.”

Of course, if Boriska is right, all those people furiously working to be the first to live, and die, on the red planet are participating in a race that has already been won. Mars, at least according to young Boris Kipriyanovich, already has a rich, and tragic, history.

“There was a catastrophe on Mars where I lived,” said Boriska. “There was a nuclear war…Everything burnt down. Only some of them survived. They built shelters and created new weapons. All materials changed. Martians mostly breathe carbon dioxide. If they flew to our planet now, they would have to spend all the time standing next to pipes and breathing in fumes.”

And how is it that Boriska survived this calamity?

“I have no fear of death,” he said, “for we live eternally.”