“Nailah didn’t understand how Jahi could be dead when her skin was still warm and soft and she occasionally moved her arms, ankles, and hips.”

This line is from an article which ran February 5th in the New Yorker magazine and in the weeks since has been among the most read articles on the magazine’s website. The piece lays out the harrowing story of Jahi McMath, a 13-year-old from Oakland California who went to the city’s Children’s Hospital to have her tonsils removed in an attempt to cure a condition of sleep apnea, but ended up in a coma. Nailah is her mother.

“When Jahi awoke, at around 7 p.m. on December 9, 2013, the nurses gave her a grape Popsicle to soothe her throat,” writer Rachel Aviv explains in the New Yorker article. But, “About an hour later, Jahi began spitting up blood” and “by nine that night, the bandages packing Jahi’s nose had become bloody, too.”

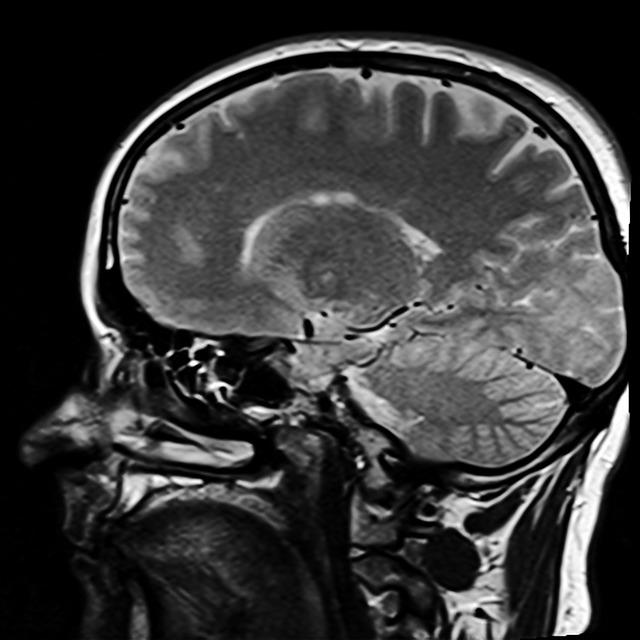

“Two days later, Jahi was declared brain-dead,” Aviv writes. “With the help of a ventilator, she was breathing, but her pupils did not react to light, she did not have a gag reflex, and her eyes remained still when ice water was dripped in each ear…On an EEG test, no brain-wave activity could be seen.”

Part of the reason the story has been getting so much attention is that Jahi McMath’s situation gets at the root of what it means to die. And this is not just an academic question, it is literally a life or death battle of science and words that pits two different-minded groups of physicians against one another. On one side are a group I’ll call the death traditionalists. They set the boundaries of death with an unshakable scientific definition. The opposing group views death more broadly—I’ll call this the broader death group. To them, death is something that cannot be defined with one simple definition. This group believes that there may be versions of being “alive” that are perhaps shallow and constrained but are nonetheless alive. It’s a powerful idea because it implies that people who for years physicians were classifying as clinically brain-dead, and thus technically dead dead, may actually still have been living.

Children’s Hospital in Oakland was on the side of the death traditionalists. The hospital, Aviv explains, was following California law, which itself was following a version of the 1981 Uniform Determination of Death Act, which says that someone who has sustained the “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead.” The hospital wanted to take Jahi off the ventilator that was enabling her to breathe and insisted to the family this was the right thing to do. The family adamantly refused.

In the following weeks, the incident drew significant media attention, and the case got heated. A local judge appointed an independent expert to examine Jahi, the chief of child neurology at Stanford University’s children’s hospital. His analysis, as reported by Aviv, matched the hospital’s conclusion. The death traditionalist view was repeated time and again in the media by physicians backing up the hospital’s belief that Jahi was technically dead and should be taken off life support. Aviv writes:

“In an op-ed in Newsday, Arthur Caplan, the founding director of N.Y.U.’s Division of Medical Ethics and perhaps the best-known bioethicist in the country, wrote, “Keeping her on a ventilator amounts to desecration of a body.” He told CNN, “There isn’t any likelihood that she’s gonna survive very long.” In an interview with USA Today, he said, “You can’t really feed a corpse” and “She is going to start to decompose.”

But as the case started to draw even more attention, physicians of the broader death view began to weigh in as well. Jahi is African-American, and the case also touched on the issue of race, and how people of color can be treated differently in America’s medical system. “African-Americans are twice as likely as whites to ask that their lives be prolonged as much as possible, even in cases of irreversible coma—a preference that likely stems from fears of neglect,” Aviv writes. “When a doctor is saying your loved one is dead, and your loved one doesn’t look dead,” Harvard Medical School bioethicist Robert Truog tells the writer Aviv, “I understand that it might feel that, once again, you are not getting the right care because of the color of your skin.”

Jahi is eventually flown in secret to a hospital in New Jersey, one of two states where families can reject the concept of brain death if it violates their religious beliefs. Here, the family could feel confident that at least the hospital wasn’t about to pull the plug on her. Alan Weisbard, who helped draft New Jersey’s expansive statute on death appears to take the broader death view. For one, Weisbard, who is a religious Jew, explains to Aviv that he doesn’t think “minority communities should be forced into a definition of death that violates their belief structures and practices.”

Calixto Machado, a well-respected physician and President of the Cuban Society of Clinical Neurophysiology flew to New Jersey and performed a series of detailed examinations on Jahi. He determined that although the nerve fibers that connect the brain’s right and left hemispheres are barely recognizable, a large area of Jahi’s cerebrum, which mediates consciousness, language, and voluntary movements, was structurally intact. Jahi is “an extremely disabled but very much alive teenage girl,” a lawyer for the family explained.

Later, Dr. Alan Shewmon, who had just retired as the chief of the neurology department at Olive View-U.C.L.A. Medical Center, analyzed videos taken of Jahi responding to commands given by her mother—for example, to move certain fingers—and concluded that the movements occur “sooner after command than would be expected on the basis of random occurrence.” There is a “very strong correspondence between the body part requested and the next body part that moves,” Shewmon stated. “This cannot be reasonably explained by chance.”

And the case continues to this day. In the spring of 2015, Jahi’s mother filed a malpractice lawsuit against Oakland Children’s Hospital, seeking damages for her daughter’s pain, suffering, and medical expenses. Last summer a county judge, based on videos from the mother and testimony from physicians like Alan Shewmon rejected the hospital’s 2013 declaration that Jahi was conclusively brain-dead. The case is expected to go to trial, meaning, as Aviv writes, “a jury will decide if Jahi is alive.”

But other important questions linger. If Jahi is not dead, and some version of alive, then just where is she right now? On what canvas are her thoughts thrown up against? What separates the fabric of her days from that of her nights? And does a day still equal a day to her, and a year a year? We don’t know the answers to these questions. But Jahi’s mother Nailah is thinking them too. “Jahi, one day,” she says, near the end of Aviv’s article, “I want to know everything you know and everywhere that you’ve been.”

Yvonne

Is Jahi still ‘alive’ today or did she die? For me, it’s about quality of life. But each person and family has to decide that. If Jahi had choice, then and now, what would she choose and have chosen? Eternal unanswered questions sadly.