The evidence is a collection of photographs from the Cammie G. Henry Research Center, at Northwestern State University, in Natchitoches, Louisiana. These images date back to the 1920s, and one shows a weary, skeletal woman in ragged clothes, hunched in a rocking chair. “Old Aunt Winnie as I saw her,” reads notes scrawled beside the image. “Darkies claim she is 127 years old, living in a one room log cabin all alone.” When Winnie died, according to newspaper clippings, she was 130 years-old, an age that if accurate would make this former slave the oldest known human being ever to have lived on earth.

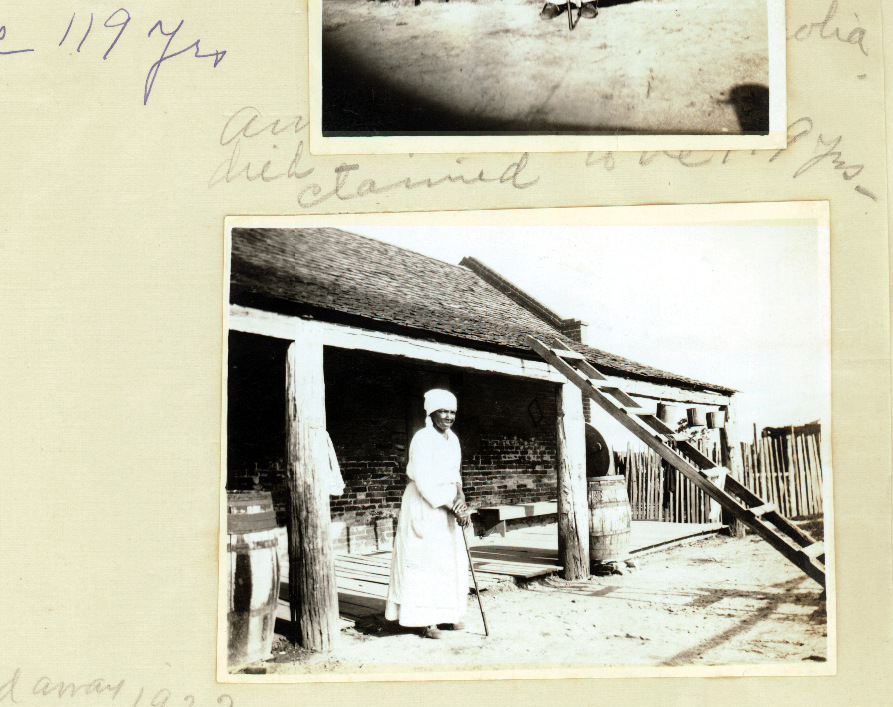

Unfortunately, we know little about the life of Aunt Winnie. But of another long-lived former Louisiana slave, Aunt Agnes, we know quite a bit more. Buried beneath the dirt floor of the cabin where she spent her later years was found a tiny sculpture made of gold depicting the voodoo deity Erzulie Fréda, and an upright Hoyt’s Nickel Cologne bottle, used by conjurers to steal people’s luck. It appears that Aunt Agnes was a practitioner of voodoo. A photo of her taken in 1922 shows a mysterious woman in a long white dress and white shawl wrapped around her head. She leans lightly on a cane, standing beneath the eaves of a small cabin. Unlike Aunt Winnie, Aunt Agnes looks prim and strong. The image was reportedly taken when she was 119 years-old, several months later she died. At that age, she would have been either the second or third oldest known human being, depending on when she was born.

“Slave or free, it did not matter at the time, the chance of anyone making it that long was very, very slim,” said Dr. Ken Brown, a University of Houston archaeologist who has excavated numerous former slave plantations, including Magnolia, the one near Natchitoches where Aunt Agnes spent the latter part of her life. “If she actually was 100, and I believe she may have at least lived to be 100, that is remarkable,” said Brown.

Keeping tabs on extremely long-lived human beings has become a potentially lucrative occupation these days. While in the United States there are presently about 55,000 centenarians, people age 100 and older, there are only about 60 supercentenarians, people age 110 and older. This means that a fair number of people live to 100, but some limiting factor or series of limiting factors prevents people from living much beyond that age. Researchers have converged around communities of long-lived people, pouring over their genomes in search of genetic gold: a gene or group of genes that may be responsible for longevity. If researchers find it, pharmaceutical companies can develop a drug to activate the gene, and we all just might be able to live super long lives.

Dr. Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, focuses on Ashkenazi Jews. Other scientists have looked at groups in Brazil, or Italy. Dr. Stephen Coles, executive director of an organization of scientists and engineers dedicated to reversing human aging called the Gerontology Research Group, or GRG, has raked the planet for genomic treasure, making notable finds in France, Japan and Jamaica. “My personal hypothesis for five years,” said an optimistic Coles, who recently published an article about his research in the journal PLoS ONE, “has been there is something in their genes that allows supercentenarians to go further.”

Scientists on Longevity Gene: Is DNA of World’s Oldest Humans the Secret to Very, Very Long Lives?

Might this gene for long lives have existed in former Louisiana slaves? Could Aunt Agnes and Aunt Winnie really have lived longer than anyone else on the planet? To make a claim with the GRG, which along with Guinness World Records keeps formal records of the world’s oldest peoples, a person needs to provide a birth or baptismal certificate, a marriage certificate and a photo ID. It seems absurd to require these documents of someone who may have been born in Africa, spent much of their life as a slave, and died before photo IDs were even invented. Nevertheless, age exaggeration is common, and improper documentation has kept people like Aunt Agnes off official lists of the world’s oldest peoples. “Let me put it this way,” said Robert Young, a Georgia-based GRG supercentenarian investigator, when asked about the age claims of Aunt Agnes and Aunt Winnie. “That’s mythology.”

But conversations with people familiar with the lives of these women and the plantation where they lived suggest a more complex situation. “I grew up knowing about traditions of these long lived people,” said Dustin Fuqua, a cultural resource specialist at Cane River Creole National Historic Park, in Natchitoches. Fuqua grew up in Avoyelles, a rural parish about an hour south of Natchitoches. “Even in my own family I have heard of people living past 120,” said Fuqua. “I laugh at that and take it with a grain of salt, but it is relatively common to hear of people from around here who have lived that old.”

Cane River Creole covers the grounds of two former Louisiana plantations, Oakland and Magnolia, which is where Aunt Agnes lived. Aunt Winnie lived on a nearby plantation, although researchers are uncertain which one. The Oakland and Magnolia plantations are unique because they remained in the same families, the Prudhomme and LeComte, for more than 200 years. In the late 18th century, these families farmed indigo and tobacco, then cotton became king and remained the main cash crop through much of the 20th century, until soybeans and corn took over. In 1994 Congress established the area as a park, citing its unique heritage.

By 1860 there were 332,000 slaves in Louisiana, about half of the state’s population. Nine out of ten slaves worked on rural farms and plantations, like Magnolia. “The men specialized in skilled work such as carpentry or blacksmithing, and the women cared for the children,” reads a Cane River Creole Park report. “The majority of slaves worked from sunrise to sunset and beyond.” A Louisiana law passed in 1830 made it a crime to teach slaves to read and write. The 2013 Oscar-winning film 12 Years a Slave portrays in agonizing scenes just how brutal life was for Louisiana slaves. Women were raped repeatedly by drunken owners and men were beaten and hung to death for petty grievances. Somehow, Agnes and Winnie survived decade after decade in an environment where this sort of treatment existed.

“In order to survive slavery one thing slaves had to do was develop a system to keep the owner and overseers the hell out of the community,” said University of Houston archaeologist Ken Brown. This meant constructing a secret world, hidden from the owners and overseers, where questions of spirituality, physicality and justice were addressed. Although this world is often absent from popular films such as 12 Years a Slave, explained Brown, within the slave community there were indeed leaders, and there were administrators of justice, and there were healers and conjurers. Aunt Agnes, he said, was most likely one of the latter.

Brown has focused his career on examining the rituals and routines black people retained from Africa and how that knowledge helped them survive slavery. He has done excavations at the Levi Jordan Plantation in Brazoria County, Texas and the Frogmore Plantation on St. Helena Island, along the coast of South Carolina. On the advice of a student, in 2005, he began work at Magnolia. What he found was astonishing. On Magnolia, slaves lived in simple wood cabins. Aunt Agnes lived in what the park service refers to as Cabin #1. Near a doorway on the western side of the cabin Brown found, buried beneath the floor, a tiny gold carving of the Virgin Mary, standing atop a pile of snakes, which themselves are covering the top of a globe.

Sculpted metal Virgin Mary’s like this one were common in the 1830s, and were referred to as miraculous metals. What is interesting about this particular Mary, explained Brown, is that she has very un-European features, namely a broad nose and large eyes. In other words, Mary had been altered to look African. Brown believes this Mary was made to represent the highest female deity in voodoo, Erzulie Fréda. Erzulie’s role was to bring messages from the top voodoo deity, Papa Legba, who consorted with the world of the loa, or spirits, down to the world of humans. The way she did that was by riding on snakes. “This is a material object associated with voodoo,” said Brown, “and it was found in Agnes’ cabin. It may not be the voodoo practiced in the Caribbean, but it ain’t far from it.”

Talking death with pharmacopeian Hamilton Morris, who traveled to Haiti in search of zombie powder

There is more. Beneath a doorway leading to a back room in Aunt Agnes’ cabin, where during the days of sharecropping men came to gamble in secret, was buried an upright Hoyt’s Nickel Cologne bottle. “Hoyt’s Nickel Cologne was an ingredient for conjurer tricks, particularly those related to luck, and particularly luck in love and gambling,” said Brown. “The bottle was standing upright, which means it accepts something. If you walked over the bottle it was intended to take your luck away, we called it the house advantage.”

The most spectacular find of all in Aunt Agnes’ cabin was an X buried beneath the floor, with pits containing artifacts at each point of the X representing the cardinal directions: east, north, south and west. These crosses have been tied back to the Congo, and parts of West Africa. In cultures of this region the cross represents a crossroads, where two paths come together only to once again diverge. The cross represents the cycle of birth and death. You are born in the east, the north represents your height of power in this world, the west represents your death and the transition to the world of spirits and ancestors, and the south represents your height of power in the spirit world. Brown refers to these crosses as “cardinal deposits”, and he has found them buried beneath the floors of slave cabins in Brazoria County, Texas, St. Helena Island, South Carolina and Cabin #1 at Magnolia.

Brown’s work has shown, against some scholarly disbelief, that the traditions of Africa managed to survive in America, even in places like Louisiana where owners were so cruel and the life of slaves so restricted that it was believed most native African traditions had been expunged. We knew from prior records that Aunt Agnes was a midwife, someone who brought life into this world, but what we know now from Brown’s work is that she was also most likely a conjurer and a curer, one who relied on the tricks of voodoo to communicate with the spirt world and to heal.

Brown pointed out that if you look closely at that mysterious photo of Aunt Agnes in the long white dress, you will see on the wall of her cabin what looks like metal wire, bent into the shape of a diamond. This is also a crossroads symbol, said Brown, and, “probably her way of advertising what she did.” But how did Aunt Agnes become a conjurer in the first place?

“The simple and unfortunate answer is we don’t know,” said Brown. The first problem lies in figuring out where Agnes was born. In 1807, Congress passed an act making it illegal to ship slaves from Africa or anywhere else into America. If Agnes indeed died at age 119, in 1922, then she was born in 1803. This means if she came from Africa she would have had to have been a child. “They didn’t really spend a lot of time bringing in kids,” said Brown. He thinks Agnes was likely born somewhere in the Caribbean, then taken to Louisiana.

Agnes appears on the Magnolia plantation sometime in the 1890s, when she moved in with one of her daughter’s families. Before that she was likely on another northern Louisiana plantation, but which one, nobody knows. Census records were not kept for slaves, all historians have to work with is a dehumanizing document called the “slave schedule”, which recorded sex and age, but no names. Parish records could indeed yield more information, such as a list of slave births within that parish, and maybe even the name at birth. “If you had a lot of money and a lot of time,” said Brown, “you might be able to look at parish records and find something.” But then again, you might not. Even where records existed, in some instances they were lost or burned.

The photo of Aunt Agnes and the notes about her age were recorded by a progressive woman named Carmelite “Cammie” Henry, for whom the research center where the photos are kept was named. Around the turn of the 20th century, Cammie Henry and her husband operated Melrose Plantation, also in Natchitoches. They farmed pecans and cotton. When Cammie’s husband died in 1918, she turned the plantation into an artist’s colony of sorts. Well-known writers and artists visited her home, including the famous New Orleans newspaperman and short story writer, Lyle Saxon and Alberta Kinsey, a renowned New Orleans painter. Cammie Henry also had her own projects. She visited plantations in and around Natchitoches, documenting life and culture. But her notes on the ages of the elderly aunts were likely based entirely on the memories of the women themselves, and their friends and family in the community.

“To make a 200 page story short, if people don’t have proof of when they are born and they get above 80 they tend to exaggerate,” said Georgia-based GRG investigator Robert Young. He points to the case of a Maryland man named William Coates, who died in 2004 and whose nursing home records indicated he was 114. An investigation into his birth records by Young revealed he was really only 92. Or there is the case of Charley Smith, who died in 1979. He claimed to be 137 years old and said that he had been born in Liberia in 1842, kidnapped at age 12 and brought to the United States where he was sold into slavery in Louisiana. Although a PBS documentary was made about his life, and in 1972 he was invited to view the launch of Apollo 17 as a VIP, Smith’s claim was later debunked. He was probably only about 100, and he was never a slave. “Like with bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster, mythology only exists where evidence is not available,” said Young.

Basically, when you have good data, you don’t get age claims over 120, and when there is poor data, you do. “The slave stories are probably between 98 and 99 percent not true,” said Young. “You have an uneducated population with no proof of birth and a longing to be connected to the past.” Young’s master thesis at Georgia State University, entitled African American Longevity Advantage: Myth or Reality? A Racial Comparison of Supercentenarian Data, discusses several different reasons age exaggeration occurs within a community.

There is the village elder myth, where a local wise man or woman is revered for their great age. The older they are the more reverential their wisdom, hence the tendency to exaggerate. There is the patriarchal myth, one of the very first longevity myths, formed in an effort to link humans to gods. Great persons, such as kings or queens or war generals can have superhuman lifespans. There is the fountain of youth myth, the idea that with the right diet or water or lifestyle a person can greatly enhance their longevity. There is the Shangri-La myth, the idea that a certain location confers extreme longevity, say high in the Andes Mountains of Ecuador, or a remote section of Pakistan. “Every culture has an age mythology,” said Young.

In the end, it seems that everyone exaggerates about age when given the chance. But there is a reason these exaggerations linger in our minds in the first place, the same reason why researchers like Coles are pushing so hard to discover the genes responsible for longevity. We want to believe that longer life is possible. And we want to believe in the human spirit, that even if given a horrible lot in life, we can triumph, and we can live. Perhaps this is why Aunt Agnes’ story is so remarkable, and why it deserves to be properly investigated.

“The next step,” said Mary Linn Wernet, chief archivist at the Cammie G. Henry Research Center, “would be to challenge people to do the necessary research.”