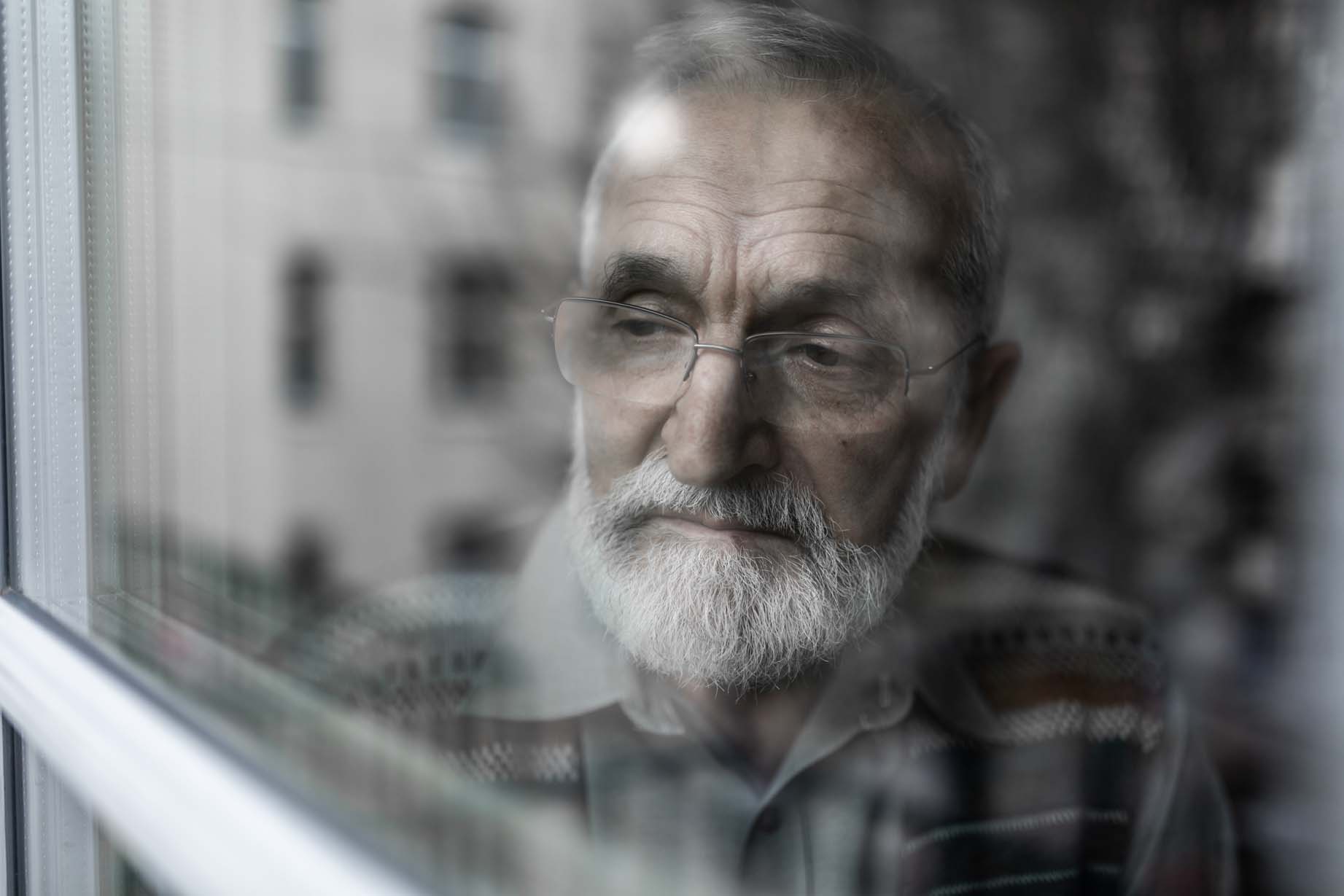

Yesterday I received a note from a colleague highlighting another aspect of the coronavirus crisis—not only are the nation’s older adults dying from coronavirus, the anxiety and isolation brought on by the virus is leading to deaths too.

“My father in law just passed away last night at age 95, in part because he was trapped in a nursing home and we weren’t allowed in to see him because of the quarantine,” my colleague wrote. “He was under tremendous stress, exacerbated by the isolation, and suffered a heart attack late last night.”

As officials work to keep pace with the rising number of coronavirus deaths, this type of lonely death may be overlooked. “Lonely death” is a topic that Digital Dying has written extensively about, and this issue certainly seems like an important trend to pay attention to as we move forward with this crisis.

“Feelings of isolation and loneliness can increase the likelihood of depression, high blood pressure, and death from heart disease” and “affect the immune system’s ability to fight infection,” wrote Abdullah Shihipar, a Brown University public health expert, in a recent op-ed for the New York Times. “Loneliness and isolation are especially problematic among older people,” Shihipar continued. The article pointed out that twenty-seven percent of older Americans live alone, and that among older people who report feeling lonely, there is a 45 percent increased chance of mortality.

“It all feels eerily apocalyptic—and, for most, scary,” said Robin Wright, writing in the New Yorker earlier this week. “The novel coronavirus has swept the globe at a time when more people are living alone than ever before in human history,” continued Wright. “I live alone and have no family, and usually don’t think much about it. But, as the new pathogen forces us to socially distance, I have begun to feel lonely. I miss the ability to see, converse with, hug, or spend time with friends. Life seems shallower, more like survival than living.”

Wright goes on to say that, “science shows us that anxiety and isolation exact a physical toll on the brain’s circuitry. They increase the vulnerability to disease—by triggering higher blood pressure and heart rates, stress hormones and inflammation—among people who might otherwise not get sick. Prolonged loneliness can even increase mortality rates.” She mentions a 2015 study by a neuroscientist and psychologist at Brigham Young University that examined the impact of social isolation, loneliness, and living alone. “The review found that loneliness increased the rate of early death by twenty-six percent,” writes Wright. “Social isolation led to an increased rate of mortality of twenty-nine percent, and living alone by thirty-two percent—no matter the subject’s age, gender, location, or culture.”

It is an issue that the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) recently addressed in an informational article. “Social isolation and loneliness can become more common with age,” the AARP article states. “And the arrival of the novel coronavirus will almost certainly make the problem worse.” People 60 and older and people with severe chronic health conditions—such as heart disease, lung disease, and diabetes—are at higher risk for developing more serious illness from COVID-19, the article notes. The article goes on to cite social isolation and loneliness as serious health issues, “the equivalent of smoking 15 cigarettes a day.”

The AARP article offers some important advice. “Remaining connected is especially important for people who live alone; regular social contact can be a lifeline for support if they develop symptoms,” the piece states. “Regularly scheduled phone calls and video conferences along with texting and emails can help compensate for a lack of in-person contact.” Furthermore, people should, “take a break from news stories and social media; hearing about the pandemic repeatedly can be upsetting.”

Other activities to decrease loneliness and depression and boost connectivity and heart power include the following. Create a list of community and faith-based organizations that you can contact. If your neighborhood has a website or social media page and you haven’t joined it, consider doing so to stay connected to neighbors, information and resources. And, regular phone calls will be increasingly important for friends and families to remain connected. Also, pets can help combat loneliness and have been linked with owners’ longevity.

But the heart can go bad in many ways. There is loneliness, and there is also heart disease. There are more than 120 million American adults living with heart disease. And as a recent article in the Washington Post pointed out, those with weakened hearts were more at risk from the virus. “As the novel coronavirus spreads around the world, it primarily sickens people by affecting their lungs,” the article reads. “But it is now becoming clear that the finishing blow for people who don’t survive might be to the heart.” The patients who end up dying, says James Town, a Seattle intensive care doctor, actually die of cardiac rather than respiratory failure.

In the case of my colleague’s father in law, shut up in a nursing care facility that was forced to restrict access because of the coronavirus, none of this was possible. This is one more of the grim realities the virus has forced upon our society. One possible result of the crisis is that perhaps the United States may start to re-examine its present system of elderly care, in which older adults often live in nursing care facilities or retirement communities far away from family.

A New York Times article from earlier in the month describes one family in western Washington state, where the outbreak hit early and hard, that decided to remove their 86-year-old mother from the Kirkland Life Care Center.

“With the aid of a hospice service, the family set up a hospital bed in the downstairs of their home, quarantined themselves from the outside world and became round-the-clock caregivers,” the article noted. “They wear gloves to serve her red wine.” The octogenarian’s daughter added, “She sacrificed so much to be the most loving and caring person we could ever know—This is why we’re doing this for her.”

In the months, and years, to come it is possible this type of move ‘back home’ may become more common.