Climate scientists have been ringing the alarm for years. Bigger storms, more floods, more droughts, more fires. And now it is suddenly seeming all too real.

Within the past few weeks flash floods have torn through Arizona and Colorado, fires have raged across California and Oregon, and on Sunday Hurricane Ida crashed through Louisiana causing catastrophic damage.

As climate change expands from a scientific theory hotly debated that seemed like it might slightly tweak the weather of some far-off future to an established fact that is altering the world and reshaping our lives, the deaths that befall us are changing too. As Digital Dying has reported across a variety of topics, climate change is not just reshaping the way we live, it is redefining how we die.

According to the World Health Organization, climate change already causes 150,000 deaths a year. And between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year, from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress. “Areas with weak health infrastructure,” says the World Health Organization, a global health agency headquartered in Switzerland, “will be the least able to cope without assistance to prepare and respond.” Other researchers have discussed the idea of compounding disasters. That is when multiple climate change-related incidents collide together making prompt responses from emergency and medical officials nearly impossible and deaths even more likely.

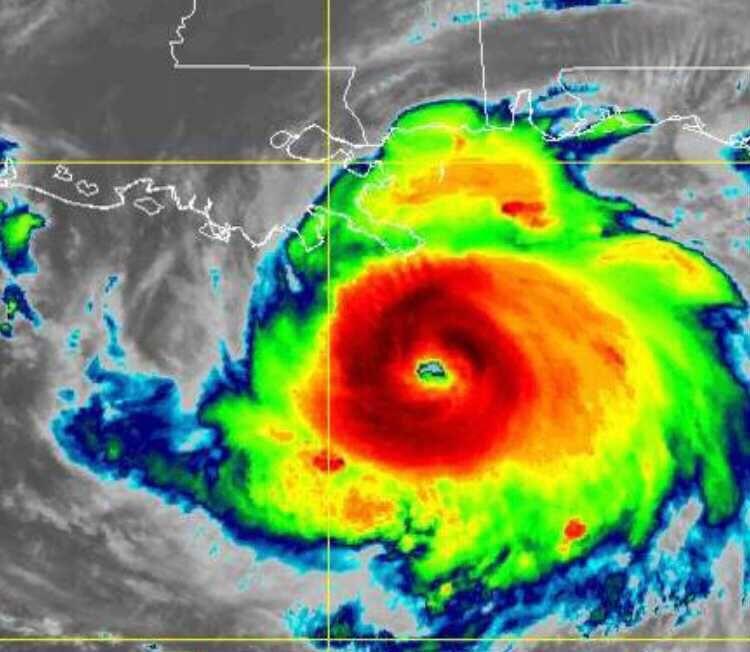

In fact, such a situation was playing out in real-time over the weekend as Hurricane Ida slammed into the coast of Louisiana as a Category 4 storm with sustained winds of 150 miles per hour. The hurricane entered a state experiencing one of the worst Covid-19 outbreaks in the nation. In the past week, New Orleans has averaged 220 new infections a day, and across the entire state, more than 3,400 new cases were confirmed as of Friday, according to the Louisiana Department of Health. At least 2,684 people are hospitalized in Louisiana with Covid-19. Unvaccinated residents account for 90 percent of new infections recorded between August 12th and 18th, and 91 percent of current hospitalizations, according to the state health department.

“Hospitals in New Orleans are bracing for public health emergencies on two fronts as Hurricane Ida threatens to strike at the same time as Louisiana is experiencing a surge in coronavirus cases,” reported CNBC. The article quoted Dr. Jennifer Avengo, New Orleans public health director. “Once again we find ourselves dealing with a natural disaster in the midst of a pandemic,” she stated. “Our plea and our hope is that everyone will prepare for both very seriously and very thoroughly.”

Throughout the last decade, Digital Dying has covered a variety of different ways that climate change can kill, in an effort to raise awareness of these serious environmental and health issues, and also highlight the trends and challenges within the profession of deathcare itself. Here is a sampling of our work, which continues to ring loud and true.

Death by Heat

While hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, and blizzards often take the headlines when it comes to weather-related deaths, it is actually heatwaves that kill the most people. As many as 12,000 people in the U.S. may die from heat each year. According to coroners in British Columbia, at least 808 people died in the Canadian province’s record-breaking heatwave at the end of June. And at least 200 people died across Washington and Oregon. In Hermiston, Oregon, a worker at a Walmart distribution center collapsed while working in an unairconditioned trailer and later died. And in St. Paul, Oregon a 38-year-old farmworker died after moving irrigation lines at a plant nursery on a day that temperatures hit 105. In Oregon, the youngest person who died from the heat was 38 and the oldest was 97, according to state officials. The average age was 66.

Digital Dying first reported on this issue back in 2017 with a post entitled, Just How Many People Will Climate Change Kill? And we published a lengthy article on the topic this past July, Temperatures Soar And A New Way Of Dying Emerges—Death By Heat.

In our 2017 post, we cited research by the American Geophysical Union. “We show that heat stress…is projected to rapidly and dramatically increase and that by mid-century crippling summertime conditions are possible across some of the most densely populated regions of the planet,” researchers stated. “By the end of the 21st century, the habitability of some regions of the planet may be questionable due to heat stress alone.”

Indeed, this Summer the temperature in Turkey and North Africa approached 122 Fahrenheit, according to Bloomberg. And Finland experienced 31 consecutive days with maximum temperatures above 25°C, the longest heatwave ever recorded in the country. Emergency rooms filled up, mostly with people suffering from dehydration and cardiac issues. And in Japan, some events for the Summer Olympics have had to be moved to cooler locations in the country because of the heat in the Tokyo area, and at least one athlete collapsed because of the heat.

As we reported in July, in France’s heatwave in 2003, CNN reported that funeral homes had to build their own coffins on the spot as morgues overflowed. City officials organized temporary burials in paupers’ graves to relieve pressure on their overburdened funeral services and Jean-Paul Proust, chief of police for Paris, explained to reporters that the city would bury all corpses left unclaimed for 10 days. “These corpses will not be buried in a common grave,” he stated, denying a local press report that unclaimed bodies would be dumped into secret mass graves. Rather, special concrete-lined graves would be marked, and families could have the caskets exhumed for a proper reburial elsewhere at a later time.

Death By Cold

Our 2015 Digital Dying article, Blizzard Deaths, Now And Then shows that in the final stages of hypothermia, the mind goes soft, like that of a child, and the body wants nothing more than to sleep. This happens to the protagonist in Jack London’s famous short story, written in 1908, To Build a Fire. The character falls into, “the most comfortable and satisfying sleep he has ever known.” He is on a remote section of the Yukon Trail, and the temperatures are an abominable -75 Fahrenheit. His final thoughts are about his friends, the boys, who he imagines will find his body the next morning. “He did not belong with himself anymore,” wrote London, “he was out of himself, standing with the boys and looking at himself in the snow.”

Apparently, it happens very much like this, the numbness of the body, the desire to sleep. And perhaps too, the realization that you have done something you should not have done. Gotten yourself into a situation that could have been avoided. “You’re lying alone in the bitter cold, naked from the waist up,” reads a January 1997 Outside Magazine article on the topic entitled, The Cold Hard Facts of Freezing to Death. “You grasp your terrible misunderstanding, a whole series of misunderstandings, like a dream ratcheting into wrongness. You’ve shed your clothes, your car, your oil-heated house in town. Without this ingenious technology, you’re simply a delicate, tropical organism whose range is restricted to a narrow sunlit band that girds the earth at the equator. And you’ve now ventured way beyond it.”

Our 2015 article on the topic also provides the example of an explosive November “Lake Effect Snowstorm” that buried the Buffalo suburbs in eight feet of snow. Much of the snow fell in one night. Many people were stranded in their snow-buried homes and about 150 cars and trucks were stranded on the interstate. At least two people died in their cars, including Donald Abate, 46, who was on his way home from work. He pulled over due to the white-out conditions. Within time his car was buried under 15 feet of snow. Both he and his family called 911, and they were told help was on the way. AAA sent a tow truck out to assist him but police turned it away, citing that there was a travel ban. After being trapped in his car for more than 24 hours, Abate died.

We also mentioned a famous case from 130 years ago, the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard of 1888. Hundreds of Minnesota and Dakota Territory children were caught outside walking home from school when a fierce January squall tore through the area. “About 3:30, we heard a hideous roar,” remembered farmer and Norwegian immigrant Austin Rollag, of Valley Springs, S.D. “My wife and I were near the barn when the storm came as if it had slid out of a sack. A hurricane-like wind blew so that the snow drifted high in the air, and it became terribly cold. Within a few minutes, it was as dark as a cellar, and one could not see one’s hand in front of one’s face.”

Snow fell in frozen horizontal sheets, accompanied by 60 mile-per-hour winds. The wind smashed windows and snapped telegraph wires. Temperatures plummeted. By late afternoon it was -47 with the wind chill in Moorhead, Minnesota. When another Norwegian immigrant, Knut Knutson, became lost outside in the blizzard his wife Seselia went outside to look for him and became so confused she froze to death under a sled just 40 steps from her front door. But the greatest trauma fell upon the children. The storm struck just as school was being let out. That morning had been warm and sunny, and many kids were sent to school without mittens or overcoats. “Ten-year-old Johnny Walsh of Avoca, Minn., froze to death trying to find his house,” reads one article we cited at the time. Between 250 and 500 people were reported to have died in the storm across Minnesota, Nebraska, Iowa, and the Dakota Territory. And “scores died in the weeks after the storm,” wrote author David Laskin in The Children’s Blizzard, “of pneumonia and infections contracted during amputations.”

It might seem like we have conquered Winter, but blizzards certainly still happen, and there is some evidence to suggest in certain parts of the country climate change has brought more of them. And our ever-complicated world means that when they do strike we may be more likely to be caught out in them, doing something. Statistics of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reveal that the rate of deaths by cold has actually increased a bit over the past half-century. Overall, the EPA numbers reveal that a total of more than 19,000 Americans have died from cold-related causes since 1979, according to death certificates. “In recent years, U.S. death rates in winter months have been 8 to 12 percent higher than in non-winter months,” says EPA. “Much of this increase relates to seasonal changes in behavior and the human body, as well as increased exposure to respiratory diseases.”

In fact, in 2019 we reported on a purely modern way to be taken by the cold in our post, How To Not Die In Your Car On Christmas In A Blizzard. We cited a 2019 case from Kelo, South Dakota, where a man perished after walking away from his stuck vehicle in a blizzard. According to a local TV station, “The outside temperature was -9 with wind chill temperatures as low as -40 at the time with blowing snow and limited to no visibility.” And in one 2018 case from Kansas, a 37-year-old woman attempting to drive through a blizzard called her boss to say she would be late for work but then never showed up at all. The following day authorities found her car surrounded by drifting snow and no footprints. The sheriff’s department believes she left her vehicle after it got stuck and walked off “in an unknown direction.” Eventually, her body was found in a field three miles away.

Killer Bees

And then there is death by bugs. Last week officials in Washington state destroyed the first murder hornet nest of the season, according to an article in the UK newspaper, the Guardian. The nest was located in the base of a dead alder tree in rural Whatcom County, not far from the Canadian border. It’s the first sighting of the year of the murderous hornets, which have bright orange heads the color of a body and black and orange striped bodies with an exceptional three-inch wide wingspan and a body that can be nearly the length of two quarters put together—the stinger is a quarter of an inch long and injects a significant amount of potent venom. Murder hornets largely prey on honeybees and other insects, conducting coordinated mass attacks on the hives of smaller bees. “The hornets fly in front of the beehive entrance, catch a bee and they fly away with it to go and cut it into pieces somewhere else,” described one French beekeeper who has dealt with the hornets.

While not necessarily aggressive toward humans, their sting is extremely painful and repeated stings can kill. While other ways of dying often receive much more attention, insects do have the ability to kill and the stinging bee and wasp and hornet families have taken their share of victims. And in fact, it is often animals that take the hit—or should we say, sting—from wasps and bees. In a 2015 post entitled, Death By Bee: When Killer Bees Attack, From Utah To Shaanxi To Wutang Digital Dying wrote about three Australian shepherds who were stung to death by a swarm of bees in Santa Ana, California. Australian shepherds, mind you, are powerful 60-pound dogs known for their toughness. And in Pantego, Texas, bees actually managed to kill a pair of horses. They strike humans too.

Texan Kristen Beauregard was with the animals and her boyfriend in the backyard when killer bees descended. She was stung 200 times, her boyfriend was stung 50 times. More than 30,000 killer bees joined in the assault. To save their own lives Kristen and her boyfriend jumped in the pool. And in Moody, Texas, Larry Goodwin, 62, was on a tractor clearing land when he pushed over an old chicken coop and all hell broke loose. He had accidentally disrupted the home of a giant clan of Africanized honey bees. His daughter and neighbors rushed to the scene but couldn’t save him. “When we got to him, he was purple,” daughter Tanya told CNN. “He had thousands and thousands of bee stings on his face and arms.” Then there is the case of British backpacker Havana Marking, who was on a trip around India when she experienced a frightening bee encounter. “I heard a low hum,” explained Havana, “which was growing louder, but I still didn’t know what it was. From a distance, the swarm looked almost like smoke, an opaque mass vibrating somewhere above me. As it got closer, I realized that this strange cloud was actually thousands of bees, each one an inch long and heading for me.” Havana put her hands over her face, curled up in a ball, and pretended she was a rock. It didn’t work, but she did survive.

So, what does climate change have to do with insect and bee deaths? According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, the number of deaths nationwide from hornet, wasp, and bee stings are at record levels and climbing. Global warming may be to blame. The CDC says that in 2001, some 43 people died from bee stings—usually, people are allergic to the poison released by the insect and go into anaphylaxis. By 2017, the number of bee deaths had more than doubled, to 89.

“Yellowjackets are responsible for most of the stinging deaths because they can sting repeatedly. Plus, they attack in swarms,” reported an article with the University of Florida Health network. “Yellowjackets usually freeze to death over the winter. But the queens survive because, unlike males, they have a compound in their blood that acts like an antifreeze. This allows the queen to start a new colony in the spring. Here’s where climate change comes in: With warmer winters becoming the norm, there are more males and multiple queens in so-called super nests. With each queen capable of producing around 20,000 eggs, the numbers quickly add up.”

Death By Flood

With Hurricane Ida is poised to dump feet of rain in a swath that stretches from Mississippi to New Jersey, this seems like a particularly important topic. In fact, just last night, as Hurricane Ida slowly rotated through south Louisiana the storm’s powerful eyewall was stuck for hours over the 30,000-person community of LaPlace, located only about 30 miles west of New Orleans. Frightening images and videos started to appear on social media that showed wind-whipped walls of water pulsing through the town. A desperate plea of messages appeared on Twitter. “A family of 10 in dire need of rescue,” stated one post, which provided the address hoping that a courageous group of volunteers with private boats known as the Cajun Navy could come to the rescue. “7 adults, 1 child. Roof caved in and water rising!!!” read another post. Apparently, around 3 am this morning as winds finally subsided a bit the Cajun Navy was able to come in and make rescues.

Digital Dying has previously reported on flooding deaths in Houston during Hurricane Harvey, and we have reported on the many Gulf Coast hurricanes that end up unearthing the bodies of the dead and sweeping them away. Surely, bodies floated out of cemeteries during Ida too, and the work will soon begin of officials such as Sheriff’s Captain Mike Mudge. Digital Dying featured him in our 2015 post, Enter The Land Of Floating Tombs. Mudge was the one who after Hurricane Katrina was charged with going out to identify and retrieve the bodies and put them back in their tombs. “You are picking up everything trying to figure out who goes where and who goes what,” Mudge stated in our story. “Each crypt has its own footprint, and by looking at the precise shape of the crypt, and the shape of the marks left in the ground back in the cemetery, Mudge can often connect which crypt floated from where.”

Still, right now the focus is on the living human beings in harm’s way. We advise everyone to follow the warnings and updates provided by their local officials and the hard-working scientists of the National Weather Service. Unfortunately, it seems that this storm, and the greater one of climate change, is not yet over—it has only just begun.