In a busy Boston neighborhood of honking delivery trucks, hard-hatted construction men and urban hospitals is the Harvard Medical School’s Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine. It is here I enter on a brisk cold April morning, looking for the Warren Anatomical Museum, whose website describes it as, “one of the last surviving anatomy and pathology museums associated with a medical school in the United States.”

I am intentionally taking a trip back in time. In the age of digital learning, when everyone from kindergarteners to med-schoolers are expected to do their learning on digital devices, I find myself wondering if our ancient way of education, which involves the eyes-on experience of being able to examine original objects, might still hold some value? In a frightening future that I can easily imagine, students spend their entire career in a digital bubble, with nary a field trip out into the real world. This scenario, of stepping away from the visceral, seems especially troublesome when it comes to medical students, who are supposed to be wizards of the human body and its fine stack of layers and fluids and defects. Meanwhile, the history of medical knowledge, as we’ve written about for this blog, is one that’s intimately acquainted with death and bodies.

“Leonardo Da Vinci, the sixteenth-century artist and inventor who painted The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa…sketched sinews, sex organs, skeletons and one of the first reproductions of a fetus in utero, all of which he obtained from corpses,” Digital Dying reported back in 2009. “In England, the demand for cadavers was alleviated somewhat by the Murder Act of 1752, which gave surgeons access to the hung bodies of murderers. Anatomy schools flourished, and the corpses of murderers did not suffice. Surgeons paid shadowy villains known as Sack’ em up men, or Resurrectionists to unearth bodies from cemeteries and churchyards.”

I am not saying we should go back to corpse snatching, I am just saying there is a potentially worrisome trend afoot—and I am not the only one saying it. There has been “a dramatic decline in the role of museums as an educational tool,” states a 2014 research article on medical school museums from the journal Teaching Anatomy. “Many factors contributed to the decline…the high maintenance costs for an optional use facility, the large amount of floor space they occupy…and the remarkably widespread adoption of information technology and multimedia in medical education, including anatomy.”

And so it is that I sign-in in the lobby of the Countway Library to see the Warren Anatomical Museum, curious what all the medical students are missing, curious what I myself have been missing? “Fifth floor,” the guard tells me, “no photos,” and I get on the elevator. Right out the door, I am greeted with a drawing of a de-skinned man with 127 different muscles labeled in Latin. I move on to the exhibit, and to call it an exhibit is generous. There are a set of glass display cases on either side of an atrium on the fifth floor. That is the museum. But the contents indeed contain something special.

There is a plaster cast from 1849 of “a laborer” with the middle finger twisted like a pretzel. There is the plaster cast of a foot with six toes. There is a very angelic white plaster cast of a boy with a “large prominent rounded tumor” welling up from the neck as if a second head were trying to emerge. There is the top portion of a cranium that has been trephined, meaning a small circular saw has been used to remove a half-dollar-sized disc of bone from the skull. There is a plaster cast of a hand with seven fully developed fingers—one index, two pinkies, two middle, and two rings. The rare malformation is called mirror hand.

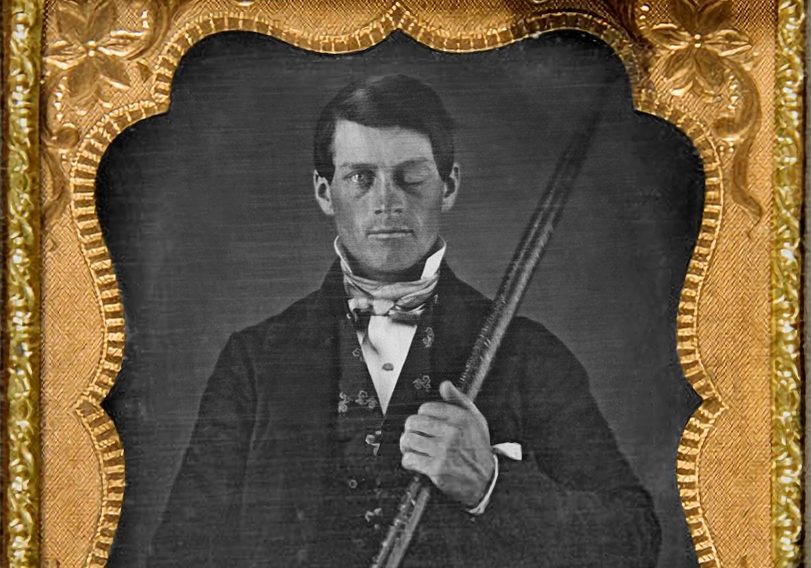

The collectors seem to have had a lot of interest in the inner workings of the hands and muscles and bones of those who performed manual labor jobs. And also an interest in what happened when such manual laborers were severely injured on the job, such as happened in the infamous case of Phineas Gage, a railroad construction foreman who in 1848 suffered an extraordinary injury. A large iron rod was driven completely through his head, destroying much of his brain’s left frontal lobe. The tamping iron, according to Gage’s Wikipedia entry, landed point-first some 80 feet away, “smeared with blood and brain.”

On display in the Warren Anatomical Museum is Gage’s skull, which was deeply examined in his own lifetime (he lived for 12 years after the accident), and yielded clues on the role different parts of the brain played in the development of human personality traits. Initially, Gage was said by friends to “no longer [be] Gage,” having suddenly become irritable and quick-tempered. Although later in his life Gage traveled to Chile, where he worked as a stagecoach driver and apparently reacquired some of his prior social graces.

Soldiers are another group the collectors have clearly taken a keen interest, as there are several examples of bodies marred and crippled by war. One severely fractured and dented skull turns out to be from “a soldier reportedly injured during the Campaign of the Pyramids under Napoleon.” There is also a scapula that has been shot through by a nineteenth-century rifle ball. And there is an 1860 US Navy amputation kit, which is as frightening-looking as it sounds. Also horrifying is an 1865 photo of a man with a shell wound to “the soft parts of the face.” Not the type of thing one easily forgets.

The museum recently hosted an exhibit on Civil War injuries (Battle-scarred: Caring for the Sick and Wounded of the Civil War) which examined the precise ways in which mid-nineteenth century metal tore apart flesh. “Even after the surrender at Appomattox and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” reads material from that exhibit, “survivors of the war faced lives marked by physical and mental disability, missing limbs, disfiguring wounds, chronic illness, and hardship.”

One of the most astonishing display items is the impossibly curved skeleton of an adult women with osteomalacia, or rickets, a condition in which the bone softens due to a lack of vitamin D. “Although donors such as Warren originally intended his collection to focus on specimens of normal and healthy anatomy for teaching,” notes one exhibit placard, “the museum nonetheless began more and more to attract donations of abnormal anatomy.”

I saw no one in the exhibit, though, oddly, through a door marked “auditorium” I heard the sound of children. Just before leaving I finally observed other visitors, a pair standing awestruck near an 1897 water-coloring of an amputated left arm. Have we hidden away death so much so that its’ true bones and bullets and smashed skulls and water-colorings of bruised bodies are lost to little-viewed exhibits on the fifth floor of medical libraries? Meanwhile, as the horror of war-shattered bones are closeted, new wars are started afresh, with new weapons and new wounds.

Later, eating lunch across town with my cousin Carmen at the Harvard Business School, she explains to me she’s aware of another hidden death-related site in this city. The tip makes sense, as Carmen has long been a fan of Digital Dying, helping to lead us to Columbine Phoenix, a maker of intricately-crafted bone jewelry—“A necklace of phalanges costs $165,” our blog reported in 2009, “and a cross of metacarpal goes for $80.”

Now Carmen is telling me to check out Mass General hospital, which features the ether dome where the world’s first public surgery using anesthetic was performed. “For some reason in the corner,” Carmen tells me, “there is a mummy—a mummy!” At least in a few nooks and crannies hidden throughout our fast-paced modern world, the emblems and items of death are preserved and live on. Though for how long, I am not so sure.