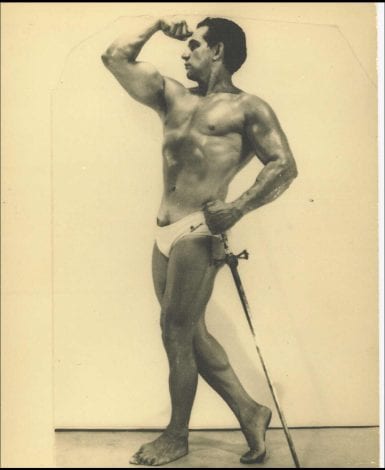

Mighty Joe Rollino was struck by a minivan while crossing the street in Brooklyn earlier this month.

At a nearby hospital, the man considered by some as “for his size, the strongest man that ever lived”—he lifted 475 pounds with his teeth and once pressed 600 plus pounds with a single finger—was pronounced dead. He was 104.

Rollino was a centenarian, a rank reserved for those who lived above 100. There may be 60,000 or more of them in the United States. A far more elite status is that of supercentenarians, those people aged 110 and up. The concept is so new it is not in most dictionaries, and according to the Gerontology Research Group (GRG), which catalogs and verifies claims, there are only 20 verified supercentenarians in the U.S. and just 75 on the entire planet.

The GRG is a mix of homespun and highfalutin. Their simple website appeals for contributions “of even one dollar per month to further research” but also states the lofty goal of “slowing” and “ultimately reversing human aging within the next 20 years.” The GRG consists of physicians, scientists, engineers, and a globetrotting clique known as supercentenarian claims investigators.

In 2006, a GRG claims investigator visited Maria Esther Capovilla in the industrial seaside city of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Born in 1889, Capovilla was 116 and at the time, the oldest living person on earth. Sadly, six months after the GRG visit, she died of pneumonia. Other GRG investigations have included the case of Mary and Rosabell Zielke, the world’s first confirmed mother-daughter supercentenarians, or that of Ruth Anderson of Minnesota, who at 110 is the oldest singleton twin—her twin brother, Abel, died back in 1900, at the age of one.

Interest in the topic is blooming, and there are a host of impressive institutions conducting research. The Supercentenarian Research Foundation is comprised by physicians from the U.S. and Europe and aims to increase lifespan for all. Boston University School of Medicine’s “New England Centenarian Study” began by looking at the genes of Bostonian centenarians, and the Longevity Genes Project at Yeshiva University’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine focuses on the genes of Ashkenazi Jews. The Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research’s International Database on Longevity is a centenarian tracking group similar to GRG.

Longevityexperts.com offers a long list of tips for attaining supercentenarianhood, anything from buying an air filter to walking three to five times a week and eating wild salmon and extra virgin olive oil. One of their tips seems more like a glimpse into a supercentenarian-friendly future: “Someday tiny nano-bots (nano-sized robots) will float through the bloodstream delivering all the nutrients that each part of the body needs, in just the correct quantities, based on each person’s genetic make-up. These nano-bots will also be able to deliver medication to exact locations in precise doses.”

The Okinawa Centenarian Study has a particularly rich sample to work with; Japan accounts for one-third of the supercentenarians on the GRG’s master list. Among the group is Kama Chinen, a woman from Okinawa who has lived for 114 years and 258 days and is the world’s oldest person. Numerous books have capitalized on the aged success of the Okinawan people, such as “The Okinawa Way: How to Improve Your Health and Longevity Dramatically” and “The Okinawa Diet Plan: Get Leaner, Live Longer and Never Feel Hungry.”

What is the secret? Much of it may indeed be diet, deep sea fish like mackerel, sardines and salmon, which are rich in omega-3 fatty acids; vegetables like peppers, broccoli, purple sweet potato, and goya, a green, bumpy vegetable related to the watermelon, and a practice of reduced caloric intake called hara hachi bu, which entails eating until you are 80 percent full and then stopping. These relatively isolated tropical islands also benefit from fresh water and clean air. A tiny island near Okinawa called Tokushima produced Shigechiyo Izumi, who died at the age of 120 in 1986, perhaps the oldest man ever to live.

Izumi’s claim was never validated by the GRG, which was not founded until the early 1990s and is generally disputed. The case raises an important question for tracking groups like GRG: How many supercentenarian lives end without being accounted for?

A New York Times article from 1897 gives the example of a man from Guadalajara, Mexico, named Jesus Campeche, who, according to the article, died at the ripe age of 154:

“He was living with his great-great-grandson and had copies of the church register at Valladolid, Spain, showing the date of his birth and baptism. According to these papers, he was born on December 12, 1742. He related incidents that occurred in the last century, showing that he had told the truth or had stored his mind well with the happenings of that time. A priest in the church he attended, who is now 84 years old, says he remembers Campeche as an old man when he was a little boy.”