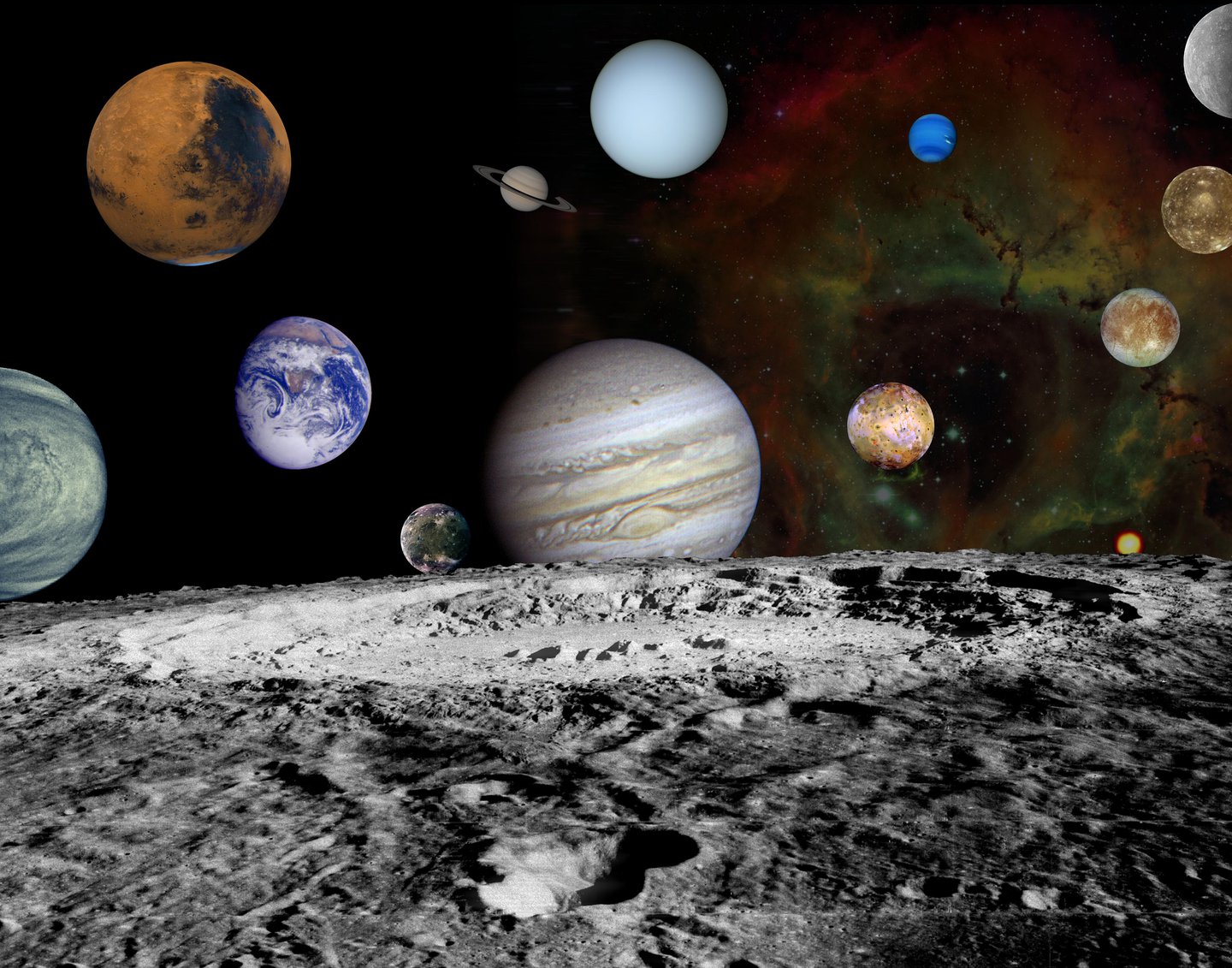

Thus far, the 18 deaths that have occurred in space have been upon exiting or entering the earth's atmosphere. Protocol regarding a death on a spacecraft or alien planet or moon remain largely undecided. (Photo Courtesy of NASA)

Earlier this month, Jeff Bezos, the billionaire founder of Amazon.com, shared with the world that he will be headed into space. While the internet has been abuzz with the richest person in America’s decision to leave this planet’s gravitational pull—for just about 11 minutes—one academic question we’ve considered here at Digital Dying is: What happens if Bezos, or any human being for that matter, dies in space?

Just about everyone on planet Earth these days is surely aware of Amazon, Bezos’s primary company. He founded it in 1994 as an online bookseller with $250,000 from his parents. They may not know that Amazon also owns a cloud computing company that provides services to Netflix, the CIA, and the oil and gas industry. And Amazon owns MGM, the Hollywood studio that makes James Bond. Amazon has a major stake in Rivian, an electric car company, and they have their own home security company, Ring, as well as the grocery chain Whole Foods. They also have an airline, Prime Air, enabling the company to ship its packages around the world. But Bezos has said that his “most important work” involves Blue Origin, an aerospace manufacturer and sub-orbital spaceflight services company headquartered in Kent, Washington. Blue Origin’s rocket ship, the New Shepard, will be taking him and his brother, Mark Bezos, to space.

“Ever since I was five years old, I’ve dreamed of traveling to space,” Jeff Bezos posted on Instagram in early June. “On July 20th, I will take that journey with my brother. The greatest adventure, with my best friend.”

Digital Dying has a long-standing interest in space. In 2012, we published a blog about Death in Space, which included information on the crew of NASA space shuttles that exploded, Challenger and Columbia, and the lesser-known story of the Soviet spacecraft Soyuz 11. This post also covered the tragic stories of the deaths of animals that were used as “guinea pigs” to test out physiological limits and biological responses to the conditions of weightlessness and zero gravity. The most famous story is that of the Soviet dog Laika.

In 2009, we published about the fascinating space travel company Celestis, which made a business out of launching cremated remains into space. “Remains are put in a capsule and placed in a rocket that travels 70 miles above the surface of the earth-space technically begins at mile 62—before descending,” our article states. “Fifteen minutes after take-off, the payload parachutes to the ground where it is recovered and validated as actually having been in space. The capsule is returned to the family as a keepsake.” The first Celestis project involved an American Pegasus rocket launched from an island off the coast of Morocco on April 21, 1997. It contained the ashes of 24 people, including the 1960s cultural icon Timothy Leary, Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, and a four-year-old Japanese-American boy who “loved to talk about the stars.”

But Celestis deals with people who are already dead going to space. What about if you are alive and then die in space? Say you happen to get shoved out of an airlock by an unruly passenger or crew member on your transgalactic voyage. The news site CNET has devoted an entire post to what happens to the unprotected body in space. “It’s a recurring horror in sci-fi: the hull is pierced, a human is trapped without equipment in an airlock about to open, a door needs to be opened in order to expel something undesirable,” the article says. “With no air and almost zero pressure, the human body isn’t going to last long without some form of protection. But what does happen, exactly?”

The article explains the first thing you would notice is the lack of air. Despite how science fiction movies sometimes depict the situation, the body would not simply explode, implode, or freeze. In fact, you wouldn’t lose consciousness straight away; it might take up to 15 seconds as your body uses up the remaining oxygen reserves from your bloodstream. After about 10 seconds or so, your skin and the tissue underneath will begin to swell as the water in your body vaporizes without atmospheric pressure. “You won’t balloon to the point of exploding, though,” states the article, “since human skin is strong enough to keep from bursting.”

And astonishingly, if you are brought back to atmospheric pressure, your skin and tissue will return to normal, and you can survive. Space also won’t affect your blood, at least in the immediate seconds, since your circulatory system is able to keep your blood pressure regulated. But, in an eerie twist, the moisture on your tongue may begin to boil. This is exactly what happened to NASA space suit test subject Jim LeBlanc, who was exposed to near-vacuum conditions in a test chamber in 1966. “As I stumbled backward, I could feel the saliva on my tongue starting to bubble, just before I went unconscious, and that’s sort of the last thing I remember,” says LeBlanc, in a historical video of the incident still available on YouTube. He went unconscious but survived and lived to tell the tale.

“If you do die in space, your body will not decompose in the normal way since there is no oxygen,” the CNET article continues. “If you were near a source of heat, your body would mummify; if you were not, it would freeze. If your body was sealed in a spacesuit, it would decompose, but only for as long as the oxygen lasted. Whichever the condition, though, your body would last for a very, very long time without air to facilitate weathering and degradation. Your corpse could drift in the vast expanse of space for millions of years.”

Which brings up a different set of questions. What are the legal ramifications of dying in space? And how would you get the body back to earth? Or, would your crewmates do what is depicted in some science fiction films and simply jettison you out a portal on the side of the craft for a modern version of a Viking funeral?

Slate reported in 2015 that a trip to and from Mars would take about 14 months, not including time spent on the planet. And there would be no other visiting spacecraft that could bring an ailing astronaut or dead body back to Earth. The Slate article notes that there have been only 18 deaths during space flights, a small fraction of the more than 500 people who have gone into low Earth orbit or beyond in the past half-century. All of those deaths have happened either while a spacecraft was lifting off or returning to Earth.

Another question the Slate article considers: “Is it OK to use the bodies of Martian settlers’ corpses for composting?”

The article quotes Paul Root Wolpe, a professor at Emory University and senior bioethicist at NASA whose job description entails thinking of all kinds of unexpected issues pertaining to human space travel, including the challenges posed by death and dying in microgravity and pondering the nature of the living crew member’s responsibility to the deceased. For instance, if someone dies six months into a multiyear mission to Mars, are the astronauts expected to store the body for burial back on Earth?

As the article says: “While it would be simple to suggest that we start incorporating some sort of mausoleum into spacecraft design, the costs would be rather prohibitive. At the moment, it costs about $10,000 for each pound a space agency puts into orbit around Earth, which means that something as simple as storing some coffins onboard a spacecraft could amount to a multi-million dollar proposal. Then there’s the psychological impact that such a morbid use of cabin space might have on the surviving astronauts.”

But the solutions NASA has come up with may not be so elegant and don’t sound anything like a warm and respectable earthly funeral or burial. Promessa, a Swedish company that specializes in organic burial solutions, has created a space body containment solution called the Body Back. It would involve first freezing the body by exposing it to frigid space temperatures for about an hour. Then the “body is brought back into the cabin from the airlock and vibrated at a high frequency, effectively shattering it and reducing it to a fine powder.” The powder is dehydrated, resulting in roughly 50 pounds of “body dust.” This dust is then stored in a container outside the craft until it is time to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere.

An additional problem with the science fiction-favored method of ejecting the body out of an airlock is that a U.N. charter forbids littering in space. “This includes corpses, even if the astronaut’s expressed wish is to have his or her body launched into open space,” says Slate.

Another problem altogether arises if an astronaut dies on another planet, such as Mars. “Disposing a body on Martian soil would probably introduce extraneous variables into further probes of the planet’s microbial life (or lack thereof),” the article continues, “making it very difficult to determine whether subsequent discoveries are of organisms native to the planet or introduced by way of decaying earthlings.”

Meanwhile, back on Earth, Bezos continues preparations for his brief space adventure.

“I’m interested in space because I’m passionate about it,” Bezos said in one interview. “I’ve been studying it and thinking about it since I was a five-year-old boy—but that is not why I’m pursuing this work. I’m pursuing this work because I believe if we don’t, we will eventually end up with a civilization of stasis, which I find very demoralizing.”

Alright—Good luck on your journey, Jeff!

The most famous coroner on earth may well be Dr. Thomas Tsunetomi Noguchi, who was…

The day after Halloween, and the day after that, is Day of the Dead, and…

Following on his recent posts regarding deaths by extreme heat, Justin Nobel shares his thoughts…

Few parts of the country have been spared from July's soaring temperatures. In fact, July…

Deep inside a South African cave called Rising Star, scientists have made an incredible discovery—a…

Last week, in Nakano City, Japan, an evacuation center was opened in the gymnasium of…