“You can skip Nevada. You can skip South Carolina. And go straight home to Delaware!”

These were the words that protestors hurled at former Vice President Joe Biden a few weeks ago outside a campaign fundraiser in midtown Manhattan in New York City. The protester’s message made the news, in large part because they showed up with a simple object that can inspire a great deal of fear and anger—a coffin.

“We made it to @JoeBiden’s Wall Street fundraiser and brought a coffin to mourn the death of Biden’s campaign,” the protesters noted.

And social media erupted accordingly, with some supporters of Bernie Sanders praising the action and other critics chastising the act and its organizers.

Present politics aside, I think it is important to note that the coffin has a long and fascinating political arc. On the one hand, a coffin is a metaphor for death—and the coffin for Joe Biden even had “Death Nails,” referencing the popular phrase, “a nail in the coffin.”

Digital Dying has written at length about the idea of the mock coffin, and its use to denote that people or objects or ideas have soured, or dwindled, or simply become unpopular.

“Around the world, people gather to mourn things that are not human, such as city services, web browsers, and political freedom,” our July 2010 article notes. “Earlier this year a New York City comedy club held a mock funeral for actress Sarah Jessica Parker.” Another mock funeral we cite in that story was perhaps even stranger:

“A bushy wreath of bright yellow, green and red flowers framed a handsome photo of the deceased: a green circle with a white G in the middle. This corpse was not a person, but the emblem for the city’s G-train subway, which hauls thousands of commuters to work each day but is not as well-used as other lines; its services are being curtailed because of budget cuts. ‘The G Train has been on life support for years,’ said one state assemblyman, ‘Now we stand here at its funeral.’”

But a coffin, of course, can also give people a reason to celebrate a life. And celebration is one of the primary purposes of our funeral tradition and its fast-diversifying array of containers and coffins. A coffin is pride, a coffin is a life well-lived, a coffin is a chance to be carried in decency on to what’s next.

“Hand built and finished throughout in the finest wood patterns, funeral caskets from Sauder Funeral Products offer revolutionary value and unparalleled appearance and quality,” states the website for Sauder, a family-owned Ohio-based company that has been constructing coffins since 1934. “Our proprietary technology makes it possible to create an affordable funeral casket that looks and feels like solid wood — for half the cost.”

But the coffin can go beyond that, a coffin can give people a chance to critique a life too. For example, in April 2013, as Margaret Thatcher’s funeral procession passed through central London, an energetic set of protestors used the opportunity to blast out their critiques of the politician and her policies.

“In London, protest organizers had called for people to silently turn their back on Thatcher’s coffin,” an article in the Guardian noted. As one disgruntled Anti-Thatcherite explained, “We have shown the world that not everyone in this country thinks Margaret Thatcher was a great thing for this country … today felt like an important moment in the battle over what her legacy is and what sort of country we want so I’m pleased our voice was heard.”

As the coffin passed, another man shouted with tears in his eyes, “She ruined my family’s life. She took my dad’s job, everything … I promised myself I would come here for this day years ago.”

Clearly, the coffin provides an opportunity to have another crack at someone.

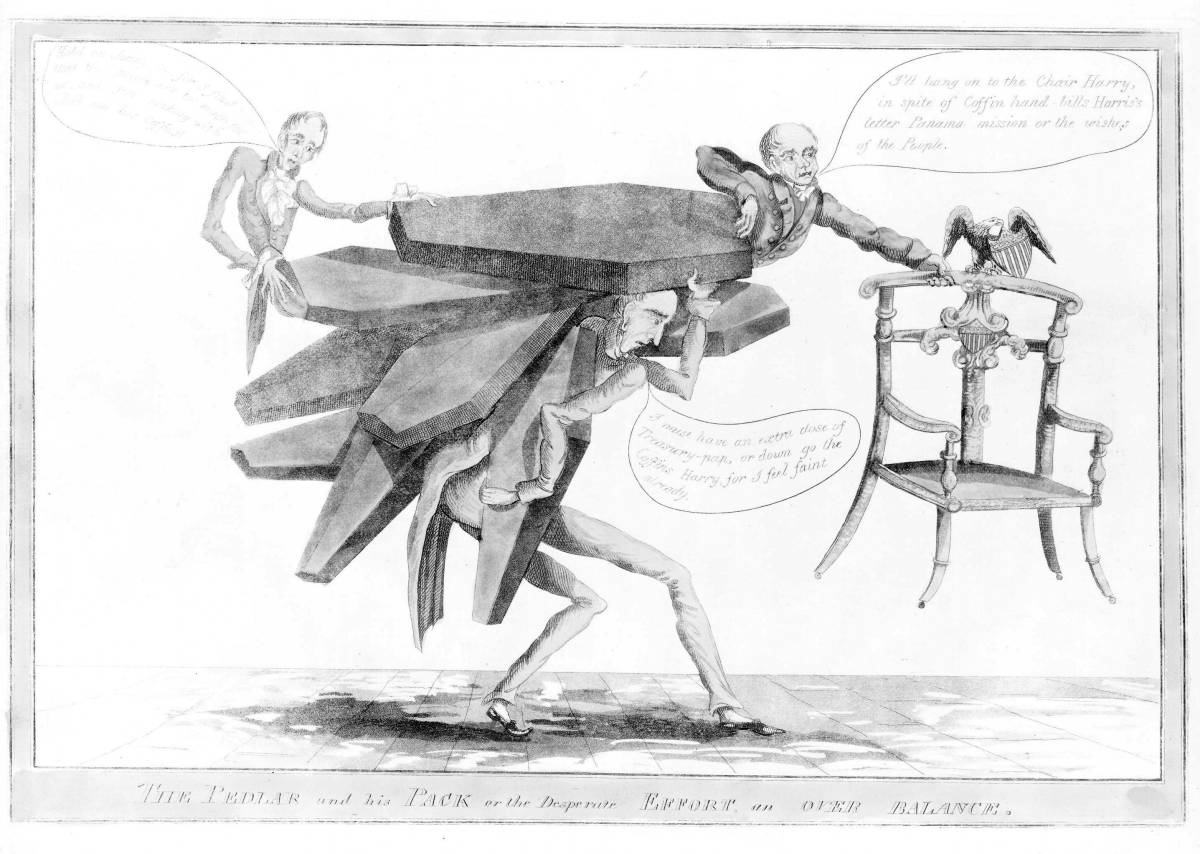

An early example of the coffin being used for political attack dates back to the “Coffin Handbills,” a series of pamphlets that attacked Andrew Jackson during the 1828 US presidential election. Jackson’s opponent was John Quincy Adams. “The campaign was very dirty, with multiple attacks on the character and personal history of both candidates,” the Wikipedia page on the Coffin Handbills states.

The first of the Coffin Handbills were published by John Binns, editor, and publisher of the Democratic Press in Philadelphia. “The poster showcased six black coffins at the top of the pamphlet and claimed that Jackson had ordered the execution of six militiamen during the Creek War,” reads the Wikipedia entry. “Another twelve coffins were displayed further down the page to represent regular soldiers and Indians who were put to death under Jackson’s command.”

More Coffin Handbills followed, focused on Jackson’s marital life and his military career. The handbills themselves became controversial, and Jackson’s opponents soon faced a backlash. The backlash entailed its own array of Anti-Coffin Handbill art. For what it is worth, Andrew Jackson won the 1828 election.

Meanwhile, as voters go to the polls in Nevada, and this election season marches forward, one thing seems certain—one way or another, we will be seeing more coffins.