Gina Lollobrigida, movie star and sex symbol, is dead at 95.

With this headline begins the obituary of Gina Lollobrigida, a famously gorgeous Italian actress who died earlier last month. She became one of the post-World War II era’s first major European sex symbols and, at one point, was regarded as the most beautiful woman in the world. She even starred in a film named “La Donna Più Bella del Mondo,” in 1955, for which she won the David di Donatello, Italy’s equivalent of the Oscar.

Gina acted beside Humphrey Bogart in the 1953 drama, “Beat the Devil,” Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis in the 1956 movie, “Trapeze,” Anthony Quinn in “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” the same year, and Rock Hudson in the 1968 romantic comedy, “Buona Sera, Mrs. Campbell.” Later, she became a sculptor and also directed her own film. She lived the enchanting life of a Hollywood star, but one doesn’t necessarily need to have lived a grand life to have a grand and entertaining obituary. Take, for example, the story of Joe Heller, a Connecticut man born in 1937 who died back in 2019, and whose obituary was written by his daughter and praised by the New York Times as: “The Best Obituary Ever…a snappy, unvarnished take on her father as one of the great pranksters in Middlesex County, Connecticut.”

The obituary draws its allure from being funny and serious, just like Joe was in life. It begins: “When the doctors confronted his daughters with the news last week that ‘your father is a very sick man,’ in unison they replied, ‘you have no idea.’” The obituary was published on September 10, 2019, and is still available on Legacy.com. “Being born during the depression shaped Joe’s formative years and resulted in a lifetime of frugality, hoarding, and cheap mischief, often at the expense of others,” it continues. But in the end, Joe was a class act and a deeply honorable man. “His service to the country and community didn’t end after his honorable discharge,” the obit continues. “Joe was a Town Constable, Volunteer Fireman and Ambulance Association member, Crosswalk guard, Public Works Snow Plower, and a proud member of the Antique Veterans organization.”

Joe Heller’s obit went viral and inspired obit writers from across the country to weigh in on its merit and the craft of obit writing itself. “I was incredibly impressed that it was written by a family member and not a professional writer, although it makes sense given the incredible level of detail and personal insight,” wrote Hannah Sentenac, a freelance writer specializing in obituaries. “I think the fact that this went viral speaks to the fact that people don’t want ‘traditional’ obituaries; they want humor, flair, wit, personality.”

An obituary of a similar order that also went viral is that of Mary A. “Pink” Mullaney, an 85-year-old Wisconsin woman who died on September 1, 2013. “If you’re about to throw away an old pair of pantyhose, stop,” begins the obit, written by her family. “We were blessed to learn many valuable lessons from Pink during her 85 years,” and top among them was never to throw away old pantyhose, but rather use them “to tie gutters, child-proof cabinets, tie toilet flappers, or hang Christmas ornaments.” Pink had many other pearls of wisdom and acts of kindness to offer, and the family laid them out for others to follow. They include bringing a chicken sandwich in your purse to church and giving it to a homeless person after the mass, going to a nursing home and offering a kiss to everyone, keeping the car keys under the front seat, so they don’t get lost, and putting picky-eating children in the box at the bottom of the laundry chute, then telling them they are hungry lions in a cage, and feeding them veggies through the slats.

Pink’s obit also recommends giving to every charity that asks and to “choose to believe the best about what they do with your money, no matter what your children say they discovered online.” And, “if a possum takes up residence in your shed, grab a barbecue brush to coax him out. If he doesn’t leave, brush him for twenty minutes and let him stay.”

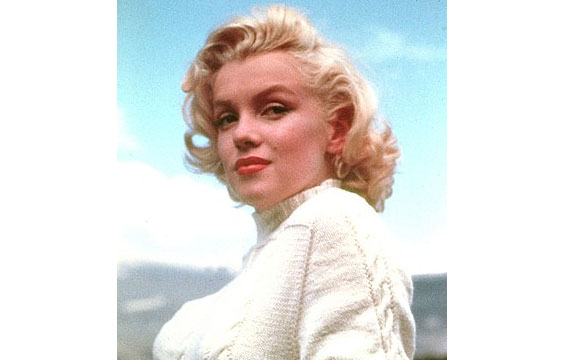

The obituaries of the rich, famous, beautiful, and glamorous offer a different sort of wisdom and a different sort of entertainment. Take, for example, the obituary of Marilyn Monroe, also known at one point as the most beautiful woman in the world. “She was swept by panics, smothered by doubts and fears, and her death had been long in coming,” reads the obituary that ran in Time magazine on August 10, 1962. “Guilt became her constant companion, and she broke promises and contracts and friendships to seek it out. She felt pulled and taunted and cheated, but when she spoke of what troubled her, her thoughts always resolved themselves so innocently that she seemed more frolicsome than frightened.”

Despite Marilyn Monroe’s storied life and many accomplishments, the most poignant part of her Time magazine obituary are the little details.

“She spent her last days alive sunbathing, glancing over film scripts, playing with two cloth dolls—a lamb and a tiger,” reads the Time magazine obit. “She went to bed early, but later her housekeeper noticed light spilling through the crack under her bedroom door and summoned doctors. They broke in through her windows and found Marilyn Monroe dead. By her bedside stood an empty bottle that, three days before, had held 50 sleeping pills. One hand rested on the telephone, and the other was at her chin, holding the sheets that covered her body.”

Marilyn Monroe is certainly not the only American star who died tragically and before their time. On February 11, 2012, the legendary “pop diva” Whitney Houston died. According to her Wikipedia page, she accidentally drowned in a bathtub at the Beverly Hilton hotel in Beverly Hills, with heart disease and cocaine use as contributing factors. “Few pop singers have been gifted with a voice as glorious as Whitney Houston’s, and even fewer have treated their talent with the frustrating indifference she did toward the end of her life,” reads an obit in the British newspaper, the Guardian. “She sold more records and received more awards than almost any other female pop star of the 20th century but spent most of her last years mired in a drug addiction that sapped her will to sing and left her in a shambolic state.”

The words of the newspaper may seem severe, but the tone here brings up an important point and notes of the difference between obituaries of the rich and famous and those of everyday people. One can be more critical of the rich and famous and still get away with it in an obituary. Whereas, an obituary for a loved one written by a family member or a close friend is typically not the space to express critiques and grievances about the departed’s lifestyle choices and manner of living. Unless of course, it is done in jest, like with the obit of Joe Heller. Whitney Houston’s obituary offers another interesting glance into the world of obit writing. It was fairly long yet published on the exact same day she died. “As a general rule, when lives are long enough, accomplished enough, and complex enough that we would just as soon not get caught short writing them on deadline, advances are assigned,” stated Margalit Fox, an award-winning New York Times obituary writer, in an article the newspaper published about “Obituaries for the Pre-Dead,” Fox notes that her colleague, the Pulitzer Prize-winning obit writer Robert McFadden, has 235 advances on file. And the paper as a whole has nearly 1,700. “I could tell you who the subjects are,” she jokes, “but I would have to kill you.”

A Slate article on the same topic points out that “the family of Sen. Edward Kennedy announced his death around 1:20 a.m. Wednesday morning” on August 25, 2009. “Within hours, news organizations had posted full-length obituaries complete with quotes from friends, family, and political experts about his life.”

News organizations prepare these so-called “advances” in one of three situations, notes Slate. “The subject is so famous that the paper would be embarrassed not to have an immediate package in the event of an untimely death; the subject is old or sick; or the subject is ‘at risk’—i.e., he’s a drug addict or a stunt biker.” For example, when Michael Jackson died at 50, “the Los Angeles Times already had an obituary ready because he had a spotty health record.” And in 2008, when Britney Spears had attained fever pitch pop stardom, her “antics were regularly featured in the tabloids” and “the Associated Press prepared her obituary despite the fact that she was only 26 years old.”

The Slate article goes on, becoming quite punchy at times: “How many obits do papers keep in the can? Depends on the organization’s size and resources. The New York Times claims to have 1,200 ‘advances’ ready, the oldest written in 1982. The Washington Post has about 150 prepped. Occasionally, this practice leads to embarrassment. Advance obituaries sometimes slip out, like when CNN mistakenly posted mock-ups of its obituary page for Dick Cheney in 2003. In 1998, the Associated Press mistakenly reported Bob Hope’s death, which was then announced on the Senate floor. Other times, the subject outlives the author: By the time Gerald Ford died in December 2006, his obituary writer had been dead for 11 months.”

But this helps explain an important difference between the obits of the rich and famous and the obituaries of everyday common people. Whereas the obits of the wealthy and famous can seem like an industrial process, reported and canned out even before the death by a professional journalist who may likely never have personally known the individual at all, the obituaries of people like Joe Heller and Mary A. “Pink” Mullaney are typically written in the moment of grief, immediately or shortly after the death has occurred, and by a close family member. While the writing may not be as sharp or widely researched as a professional obit, it has the tone of the familiar and the details only those closest to the deceased can provide. And also, perhaps the author, because they know the person so well, has more room to take creative risks in the writing and tell jokes or be cute and sarcastic.

Margalit Fox, the New York Times obituary writer, in her stunning essay offering hard-earned, if somewhat macabre professional insights into her craft, brings it back to herself. For even an obit writer, at some point, will need an obit. “Sometimes, late at night, as I lie awake haunted by the press of the pre-dead — and by the knowledge that I will one day no longer walk among them — I catch myself wondering: Is my byline one The Times will choose to keep?” writes Fox. “Who can tell? But I have miles to go before I sleep.”

“In the end, we all become stories,” notes an NBC article on obituaries by writer Nicole Spector. “Ashes to ashes and dust to dust, sure, but also: words to words. Writing doesn’t get much more meaningful than that, and there’s nothing quite so moving as an obituary that truly captures and honors the spirit of the deceased.”

>See our “How to Write an Obituary” page on Funeralwise.com.

>Read “The Self Penned Obituary” on the Funeralwise.com Forums page.