In Italy last week it happened again, three people ruined by the financial crisis committed suicide.

A couple in their sixties from Civitanova Marche, a small city of about 40,000 people on the Adriatic Sea in eastern Italy hung themselves. They had been unable to pay their rent.

As if out of a tragic novel, upon hearing the news the woman’s brother then flung himself into the ocean.

“This is a state killing!” mourners cried out to officials at the funeral, referencing the countries lingering fiscal crisis, Italy’s longest recession since World War II. According to a large Italian employee federation, since the crisis began some 62 Italian business owners have committed suicide.

Other Great Reads: Star-child suicide and accidental deaths, from Sage Stallone to Cheyenne Brando

In March of last year, a builder named Giuseppe Campaniello set himself on fire outside a government tax office in Bologna.

But Italy is not alone, across Europe there has occurred a disturbing spate of suicides linked to the recession.

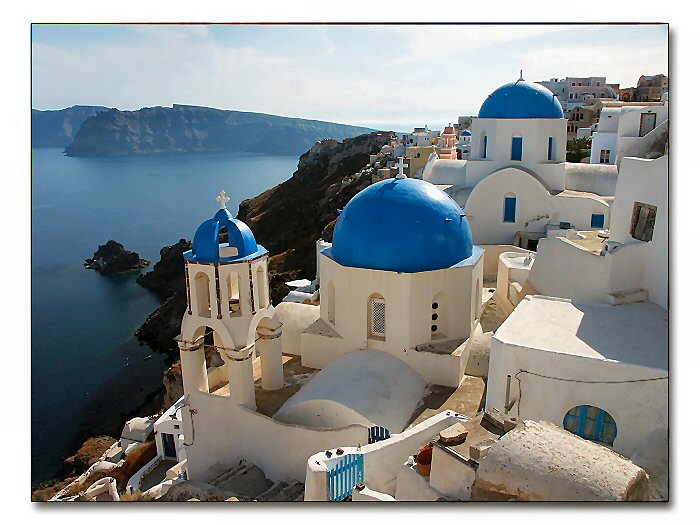

The Suicide Problem in Greece

Last May, in Greece an unemployed musician named Antonis Perris who had run out of money to buy food committed suicide.

“I have no solution in front of me,” he wrote in an online forum. The next morning he and his 90 year old mother held hands and jumped off the roof of their apartment building together.

The suicide issue has become something of a national crisis in Greece.

“A sun-kissed land with once the lowest recorded suicide rates in Europe, Greece has seen a huge spike in people taking their own lives,” read a recent article in the Daily Mail.

In June of 2012 there were 50 suicides and 350 suicide attempts in Athens alone

Other Great Reads: How to deal with grief after a suicide

Many of the suicides were carried out in public, often in violent and theatrical ways.

Like that of Dimitris Christoulas, the 77 year old pharmacist who shot himself in the head right outside of Parliament on Syntagma Square in downtown Athens in April of 2012.

A suicide note found near the scene explained that the retiree could not face the prospect “of scavenging through garbage bins for food and becoming a burden to my child.”

Meanwhile, a 2012 study in Ireland linked a rise in suicides, especially among men in their thirties, to the ongoing economic recession.

A study by the National Suicide Research Foundation looked at 190 cases of suicide in Cork City and county between September 2008, right when the economy fell to pieces, and March 2011 and found that the victims were often men in their mid-thirties. Almost 40 percent were unemployed, and 32 percent worked in construction.

Suicide Lessons From Asia

It’s a situation much of Asia is already familiar with.

After the 1997 Asian currency crisis, suicide rates among men rose 45 percent in South Korea, 44 percent in Hong Kong and 39 percent in Japan.

“A lot of Asian people just work without any other things to make life more interesting,” explained the director of the Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention in Hong Kong. “If they lose their jobs, it throws their life into total disarray.”

Other global economic meltdowns have had similar effects. In 1929, just before the Great Depression, suicide rates in the United States were about 14 suicides per 100,000 people. By 1932, the figure had increased to 17.4 per 100,000, the highest it has ever been.

In Asia, the earlier crises have led to a number of initiatives to combat suicides. One of the more interesting measures has been in South Korea, where many suicides take place in the subway. In order to prevent people from jumping in front of trains protective barriers have been installed. Stations also play “suicide-prevention music”.

“Between the roar of incoming trains, the soothing strains of Beethoven’s Fur Elise or Ben E. King’s Stand By Me float across the platforms,” explained a USA Today article from 2004.

There are 76 songs in total on the suicide-prevention soundtrack, including Send in the Clowns, by Frank Sinatra, Sailing by Rod Stewart, and Simon & Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water.