CELEBRITY DEATH HOAXES JUST KEEP COMING

Poor Jackie Chan. Not only has the movie star died once, but twice. Not really. But he has been the subject of at least two celebrity death hoaxes. The most recent was just last week. The action movie star debunked the most recent report by taking to his official Facebook page to let his fans know that he is still very much alive and kicking.

Gallery of Celebrity Death Hoaxes

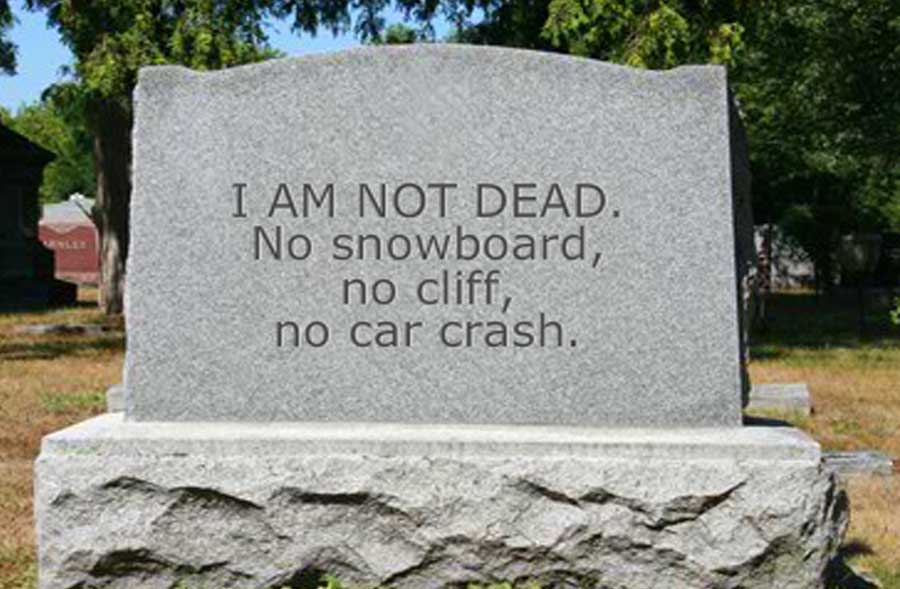

Chan is not alone. Eddie Murphy, Paris Hilton, and Tom Cruise have all been victims of repeated social media death hoaxes. In fact, these days rarely a week goes by when a Twitter feed, blog post, or Facebook page doesn’t mention the death of one of our favorite stars. In our own research, we came up with more than 70 celebs that have been victims at least once over the past few years. And that’s not all of them. Most of these have met their fate by a car crash, snowboarding accident, or falling off a cliff while filming in New Zealand. These are the most popular causes of death used by current hoaxers.

It’s pretty obvious that easy access to social media is a contributing factor in the widespread proliferation of celebrity death hoaxes. Websites like fakeawish.com and Global Associated News allow (encourage) you to plug-in a few details to create your very own hoax. Within seconds, you have documented the death of the celebrity of your choice. Simply post the story to your favorite sites and you can officially become part of the problem.

In March 1708 Jonathan Swift, writing as Issac Bickerstaff, predicted the death of John Partridge, an astrologer. After Partridge proclaimed he was alive Swift offered proof under his own name of the death.

There is more to it than easy access, however since the phenomenon is not new. The first documented case showed up in the writings of Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels. In 1708, Swift, writing under the name of Isaac Bickerstaff, published a eulogy for a popular astrologer, John Partridge. Swift had taken issue with Partridge’s writings and the hoax was his way of doing something about it. While Partridge was eventually able to convince the world he was still alive, it took years to overcome the effects of the hoax.

In 1945, shortly after the death of Franklin Roosevelt, word spread that both Charlie Chaplin and Frank Sinatra had died. Of course, neither had.

According to those who study the phenomena, it is quite common for a real celebrity death or a tragic incident to trigger a flurry of fake death accounts. Like FDR’s death, a number of bogus stories popped up following the death of Michael Jackson and on the heels of 9/11.

The biggest and baddest celebrity death hoax showed up way before the Internet. In 1967, a story began to circulate that Paul McCartney had died in a 1966 automobile accident. Following the rumor, fans began to examine lyrics, analyze photos and look for evidence where ever they could find it. By 1969 dozens of theories regarding the death were being put forward despite the Beatles’ camp strongly disputing the rumors. The McCartney death hoax is now legendary and has spawned television shows, books, parodies, and songs.

The iconic “Abbey Road Cover” that is said to be packed with clues pointing to Paul’s death. Among the supposed clues are the band’s attire: John Lennon leads in a white suit and symbolizes the preacher; Ringo Starr is the mourner, dressed in black; George Harrison, in scruffy shirt and trousers, denotes the grave-digger; Paul is wearing an old suit and is the only one who is barefoot. (from dailymail.com 8/8/09). (Photo Source: feelnumb.com)

In general, psychologists attribute hoaxes to the desire to get attention, defraud others, put forward an agenda, target specific individuals or groups, or just have some fun. In the case of celebrity death hoaxes, it is likely that personal entertainment is the most common motive. The perpetrators just want to have a little fun by seeing what happens. But there can be more nefarious motives since Internet perpetrated hoaxes can be link bait which will lead the clicker to a phishing, malware, or other type of destructive sites. The goal could also be simply to generate clicks for the site publishing the hoax. Fake news sites, for example, get much of their traffic this way.

This begs the question, what is the harm? Aside from the time wasted responding to the reports and the further stretching of our trust in what we read, we should remember that each and every celebrity who is reported on has family and friends. Most stars respond with humor and grace, but a few have actually spoken up about the pain caused by the hoaxes. Celine Dion, for example, expressed concern for her mother and Chloe Grace Moretz called out the creators of the hoaxes as “sick.” Morgan Freeman’s spokesman, responding at the time of a death hoax about Freeman, advised people to stop believing what the see on the Internet.

There is very little celebrities can do to stop the hoaxes. For us, the readers, the best thing we can do is to move right past them. Do not forward, do not comment, and do not re-post them. And, of course, especially if the death report includes any talk of snowboards, car crashes or falling off a cliff, do not believe them.

How to spot a fake death report (From “Wayne Knight death hoax: How and why these hoaxes happen — and how to stop them“)

Hoaxes do, in fact, make great teachable moments, which might explain why we seem to react with just a bit more skepticism each time they crop up. Here are some things to keep in mind the next time you spot one:

- What’s the source? Is it a Website you’ve heard of? If yes, is it the correct URL for that Web site?

- Is there a byline on the story? Breaking news stories will usually include the reporter’s name; hoaxes, mysteriously, go un-bylined. Does the story use proper grammar and punctuation? The first line to this Wayne Knight story should’ve been a tip-off: it’s a run-on that refers to Wayne Knight, weirdly, as “better known to most for playing one of the most indelible roles on NBC’s Seinfeld.”

- Does the story name sources? In the case of a death or accident, information should come from a local hospital, police department or medical examiner’s office. “A spokesperson for the first responders” is too vague.

- Does it mention the possibility of the news being a hoax? This is a dead giveaway.

- When you Google the images in the post, does something else come up? Right-click any picture and select “search Google for this image.” A picture that purportedly showed Wayne Knight’s totaled car actually came from a 2009 story about slick roads in Washington County, Oregon.

- When you Google for more information, what comes up? This is the real test. If a major actor really died outside of Buffalo, N.Y., local media — not to mention wire services, like the Associated Press — would be on it long before US Magazine.

Read the full story

Further reading: