A blizzard is bearing down on New York City, so it’s a good time to talk about blizzard deaths. Usually, this means freezing to death, either stuck in a vehicle on the highway as your gas slowly trickles dry or stuck outside; the infamous story of the farmer who stepped out the front door to check on the cows but never made it to the barn, just 50 feet away.

In the final stages of hypothermia, the mind goes soft, like that of a child, and the body wants nothing more than to sleep, as happens to the protagonist in Jack London’s famous short story, written in 1908, To Build a Fire. The character falls into “the most comfortable and satisfying sleep he has ever known.” He is on a remote section of the Yukon Trail, and the temperatures are an abominable -75 Fahrenheit. His final thoughts are about his friends, the boys, who he imagines will find his body the next morning. “He did not belong with himself anymore,” wrote London, “he was out of himself, standing with the boys and looking at himself in the snow.”

Apparently, it happens very much like this: the numbness of the body, the desire to sleep. And perhaps too the realization that you have done something you should not have done. Get yourself into a situation that could have been avoided. “You’re lying alone in the bitter cold, naked from the waist up,” reads a January 1997 Outside Magazine article on the topic entitled, The Cold Hard Facts of Freezing to Death. “You grasp your terrible misunderstanding, a whole series of misunderstandings, like a dream ratcheting into wrongness. You’ve shed your clothes, your car, your oil-heated house in town. Without this ingenious technology, you’re simply a delicate, tropical organism whose range is restricted to a narrow sunlit band that girds the earth at the equator. And you’ve now ventured way beyond it.”

Just last November, an explosive lake-effect snowstorm buried the Buffalo suburbs in eight feet of snow; much of the snow fell in one night. Many people were stranded in their snow-buried homes, and about 150 cars and trucks were stranded on the interstate. At least two people died in their cars, including Donald Abate, 46, who was on his way home from work. He pulled over due to the white-out conditions. Within time, his car was buried under 15 feet of snow. Both he and his family called 911, and they were told help was on the way. AAA sent a tow truck out to assist him, but police turned it away, citing that there was a travel ban. After being trapped in his car for more than 24 hours, Abate died.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) suggests keeping the following in your car or truck: blankets/sleeping bag, flashlight with extra batteries, knife, high-calorie non-perishable food, water-proof matches to melt snow and a small can to melt it in, sand or cat litter, a shovel, a windshield scraper, a tool kit, a tow rope, jumper cables, a water container, a compass, road maps.

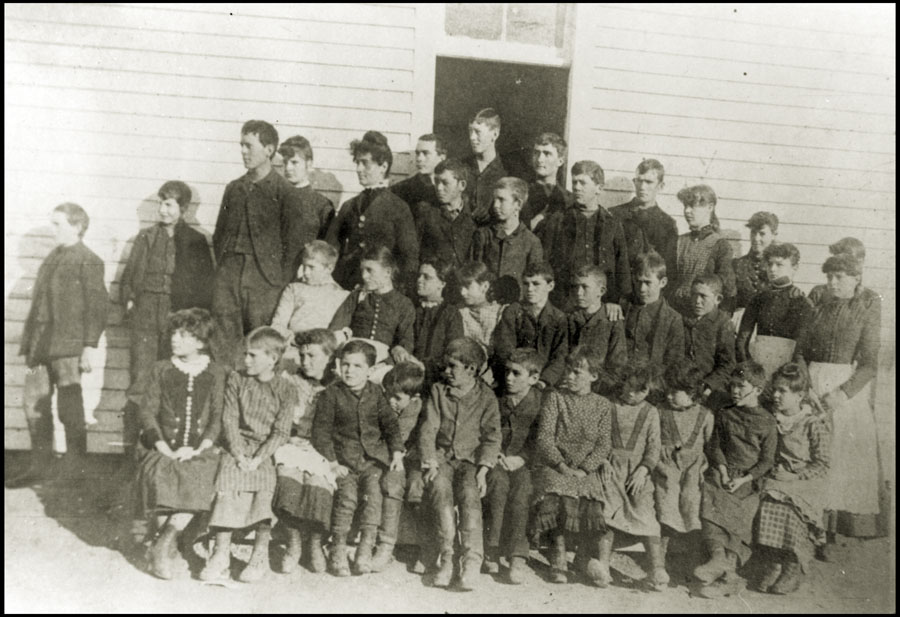

But before, there were automobiles, and snow tires and chains, jumper cables and flashlights; there were feet and boots, and hopefully, they were good boots, and hopefully, your mom made you wear your long underwear and hid an extra sandwich somewhere in your rucksack. If you were one of the hundreds of Minnesota and Dakota Territory children caught outside walking home from school on January 12, during the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard of 1888, it just might have saved your life.

“About 3:30, we heard a hideous roar,” remembered farmer and Norwegian immigrant Austin Rollag of Valley Springs, S.D. “My wife and I were near the barn when the storm came as if it had slid out of the sack. A hurricane-like wind blew so that the snow drifted high in the air, and it became terribly cold. Within a few minutes, it was as dark as a cellar, and one could not see one’s hand in front of one’s face.”

Snow fell in frozen horizontal sheets, accompanied by 60-mile-per-hour winds. The wind smashed windows and snapped telegraph wires. Temperatures plummeted. By late afternoon it was -47 with the wind chill in Moorhead, Minnesota. When another Norwegian immigrant, Knut Knutson, became lost outside in the blizzard, his wife Seselia went outside to look for him. “She became so confused she froze to death under a sled just 40 steps from her front door,” reads an article on MinnPost, based on the 2004 book by David Laskin, The Children’s Blizzard. Another local, “Hanley Countryman of Alexandria was trekking back to his house with 40 pounds of provisions and lay down in the snow to die just 150 yards from his threshold.”

Scottish immigrant farmer James Jackson discovered his cattle herd just outside Woodstock, frozen solid, although a few were still alive. Back at the barn, Jackson tried to thaw them out, but their frozen flesh came off in chunks.

But the greatest trauma fell upon the children. The storm struck just as school was being let out. That morning had been warm and sunny, and many kids were sent to school without mittens or overcoats. “Ten-year-old Johnny Walsh of Avoca, Minn., froze to death trying to find his house,” reads the MinnPost article. “Six children of James Baker froze to death while trying to make it home from school near Chester Township, Minnesota. They were found with their arms entwining each other in the snow.” Between 250 and 500 people were reported to have died in the storm across Minnesota, Nebraska, Iowa, and the Dakota Territory. “Scores died in the weeks after the storm,” writes Laskin in The Children’s Blizzard, “of pneumonia and infections contracted during amputations.”

Some two months later, on March 12, an even greater blizzard struck. Or maybe it just hit a more populous area, but it was the Nor’easter that buried New Jersey, New York, and New England in as much as 58 inches of snow and spawned drifts 52 feet high that became known in the record books as the Great Blizzard of 1888. From Chesapeake Bay to Maine, more than 200 ships were grounded, and railroads in Connecticut were drifting under with snow for eight days. More than 400 people died from the storm and the ensuing cold, including 200 in New York City alone.

Let’s hope the present blizzard bearing down on New York isn’t anywhere near as bad.