The year is 1969. Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. have recently been assassinated. Riots have swept many large American cities. And now a vibrant and subversive new music form called Rock n Roll is sweeping the nation and about to have its largest coup yet, a massive muddy marijuana-filled outdoor festival called Woodstock.

You weren’t there, but your father was, and now he is dying. You are going through the items of his life, and you are faced with the question that so many grieving family members are faced with: How best do I honor him?

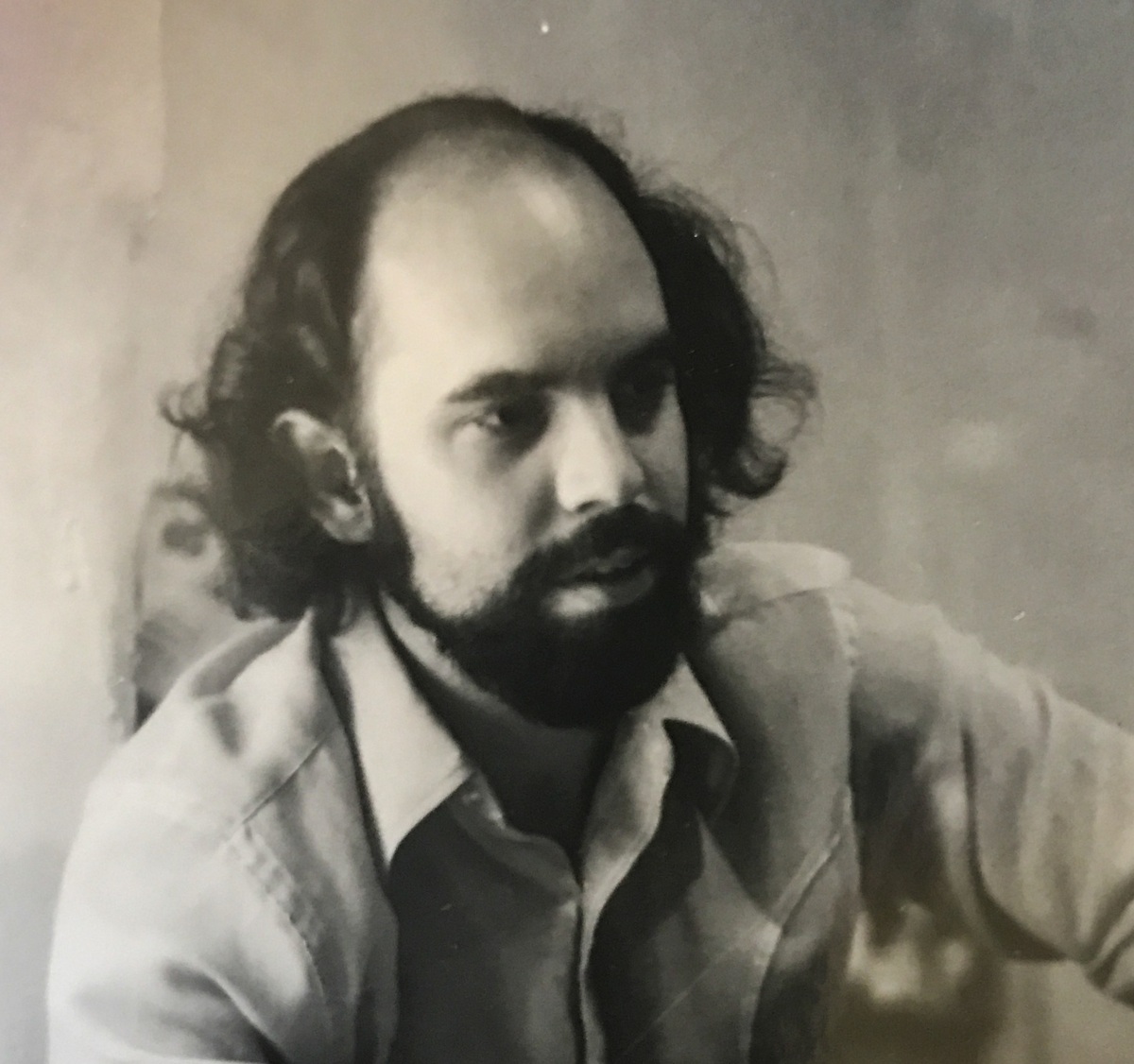

Thomas Procter Lippincott spent his life with words and music. During the turbulent decades of the 1960s and 1970s, he worked as a journalist in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, writing for among other outlets, the glossy New Left political publication Ramparts Magazine. Later, he was involved with creating a research center that aimed to transform U.S. foreign policy in Latin America. Back in the States, he wrote for the notorious New York City underground magazine Rat and The Village Voice, Liberation News Service, Down Beat, Newsday and The New York Times. Procter interviewed Bob Marley and the Wailers, Toots Thielemans, Jerry Garcia, Patti LaBelle and Joan Baez. He experienced and appreciated the creative musical fire that burned through his generation, but he also saw the perils the movement faced.

“The fact remains,” Procter wrote in a powerful 1970 New York Times essay entitled The Culture Vultures, that “our groovy ‘alternate’ subculture…continues to be dampened by a fundamental conflict: the attempt to develop a truly human, revolutionary lifestyle within the confines of an exploitative commercial system.”

“Music is meant to be dug for its own sake; not traded and sold as a market commodity,” he continued. “Those who control these enterprises feed off of us by commercially and hermetically packaging and selling back our subculture to us at outrageous prices…We must continue to wake up if our music is to be effectively reclaimed (and it will never be completely so, as long as capitalism defines our society).”

It’s quite a statement, and it is one that still rings true today. Proctor’s son Jonathan Lippincott always knew his father was involved in the sixties subculture scene (“he would often just very nonchalantly tell a story, like this one about when he spoke with Jerry Garcia,” said Jon), but he didn’t know the full breadth of his father’s life and work until his father developed dementia, and then later a condition known as Primary Progressive Aphasia, in which Proctor slowly lost the ability to process language. Jon moved from Seattle back to New York, where he had grown up, to spend time with his father. He watched firsthand how a man who had made his living processing language, slowly lost his ability to do just that.

Digital Dying recently spoke with Jon about some of his struggles and emotions in dealing with his father’s death. To help him and his family cope Jon decided to create a lasting and unique digital tribute to his father, in the form of a website with all of his interviews, radio shows and stories, and a Smartphone app. The act allowed the two, who had not always been so close, to come closer together than ever before.

How did your relationship change with your father as he was dying?

We always kind of missed each other. He had a very apologetic way about him with me, like he was walking on eggshells. When he got dementia he was really weird at first. But then it got to the point where the outer shell of his personality changed and he was completely different. Suddenly, he was very direct. You’d ask him a question where in the past he would have been passive and now he wasn’t. It became very easy to be around him and communicate with him. And it was much easier to understand where he stood and how he felt about things. He was losing his language, but all the anxiety between us completely vanished, and I was suddenly able to have a much more real relationship with my dad.

How did your father develop dementia?

After music writing, sometime in the late 1980s, he began working for a PR agency, and he worked there for like 20 years. When he retired from that he got very depressed. It was like he fell off a cliff. He didn’t know what to do. Suddenly he was about 65 and didn’t have the satisfaction of his job to be churning on every day. He was looking for ways to get back into writing, I think he wanted to do a column in the Times. Then he fell a number of times, once while walking the dog in Washington Square Park, and another time while trying to bring a big bag of dog food up the stairs. He fell over the banister and fractured almost all his ribs, I didn’t even know he had that many ribs. I flew from Seattle right away, first flight I could get. I walked into that room and it was total darkness and I found him back there in a gown with no underwear, just back there exposed, and he was looking around with wide eyes as if he was on drugs or something and he was like, “Jon…Jon…” He was happy to see me but also panicked. That was dramatic.

What inspired you to do this project, and memorialize your father?

It just happened organically. I began when my dad was still alive. I thought this was something I could do that was going to make the atmosphere brighter. I am going to bring warmth to this house where death is in the air. I am going to make my mom really happy and make my dad feel really loved. We had found these articles and the radio shows, all these boxes in the basement in my parent’s house in Vermont. There was this cache of raw tapes with interviews he did with people like Joan Baez and Ricky Nelson and Patty LaBelle. It was just cool to hear his voice, and interesting. He sounded like a totally different person, and I was like, oh man I really want to hear more of this. But some of the audio was in really bad shape, almost inaudible. I had to digitize the tapes, and then process the interviews.

I would show the site to him as I worked. I thought it might make him feel appreciated, and that other people could appreciate it too, even after he was gone, and feel joy. That’s how I framed it to him. I am going to try and get your work out to the world so people who are interested in this stuff can find it and follow it. And that made him happy. It was probably a distraction for me too, from the reality. I felt like I was doing good, I was solving this problem. It was very cathartic. It was a way to grieve. You are getting work done and you can see that. Otherwise grieving is very abstract, and you can get really upset – of course, I did that too –, but this was something that I could do and see the progress of, and it made me feel way better afterward.

How does the app component work?

The app hasn’t been approved yet for download, there are some bugs, but the people who are helping me test it can still access it, and one of them is my mother. The nice thing about the app is it has allowed her to take out her phone and listen to one of his radio shows from awhile back. And that has made her feel good, and that helps her grieve. She feels like he is there with her, and all these memories she had of the times when the interviews were recorded come back to her. All these things he was talking about. She could have gone through the material herself, and she probably would have, but now it’s in her pocket at any time. She can pull out her phone and hear her spouse’s voice and connect again. It made her so happy. And it also made her happy to see that I cared so much.

The obituary your family wrote for your father says there was “music playing until his final moment,” what music?

Yes. My sister’s partner, Francisco, and I had gotten him an iPhone and I downloaded all his favorite albums. He was obsessed with the jazz guitarist Jim Hall, who he had met, by coincidence, in New York City as they were walking their dogs. My dad had dementia by this point. When he was in rehab I bought him really nice headphones and this Bose speaker system, so he could plug his headphones in and that made it very easy for him to listen to music. He was always listening to music. It was usually Jim Hall. The morning that he died, I can’t remember, but I think I had put on Johnny Cash. His breathing was very labored, his body was shutting down. At some point my mom said, “I want to turn the music off.” And we turned the music off and he died shortly after that. We watched him die. I thought we would be playing music until he actually died, but there was something about the music that was playing that was upsetting my mom, so we turned it off. She wanted silence, like a pure moment or something. That was in Vermont, in July.

***

Jon has since returned to work, his sister has had a baby, which he said has “really elevated” his mother’s level of happiness, and the world moves on, much as it did when Procter was a young man. Culture and music are produced. Culture and music are consumed. Corporations get richer.

But idealists will always have their ideals.

“We can’t be free until everything is free,” Procter wrote in his 1970 New York Times Culture Vultures article, “because money’s what’s used to control things. The money game even controls the Man. He tries to market the moon; he figures out ways to keep people working at jive jobs, making things nobody needs so they can afford to buy things nobody needs. While we sit around grooving, the rock moguls are cleaning up and using our bread to influence the charts and control the ‘stars’…and telling us that revolution means buying their stuff!”

“If businessmen in beads and cops in bell bottoms (Woodstock Festival) is revolution how come the war’s still going on in Vietnam and the ax is coming down at home? If this is the Age of Aquarius, why do people get busted when they try living Real Lives? If this is It, baby, why is it that the same corporations which are into robbing Latin America of minerals, oil and sugar and selling it back to them to ‘help them develop’ are the same corporations which are packaging and selling our ‘revolution’ back to us? Dig it. Everybody look what’s going down…”

Some of Procter’s articles, radio shows, and interviews can be found at tplippincott.com.

Phil Gelfer

I believe your father did an article on a Junior High School student bluegrass band that I brought to a competition back in the 80’s it was in the Arts and Leisure section wish i had a copy of that